Reviews

Fiction Review by L. Chris Fox

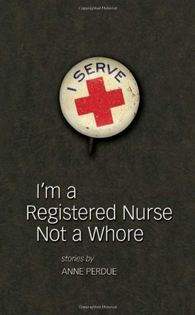

Anne Perdue, I’m a Registered Nurse Not a Whore (London: Insomniac, 2010). Paperbound, 258 pp., $16.95.

Anne Perdue’s I’m a Registered Nurse Not a Whore is a strong shortstory collection. Her deft language describes people on the workingclass edge of middle-class comfort. Set primarily in an unnamed Toronto, Perdue’s work is evocative of place and person. Physically, there are the ravines, the Danforth, and typical Toronto daytrips to The Falls and the Kawarthas. Toronto’s multicultural character is also present, although Perdue’s main characters, like John, the struggling photographer father in “Theories of Relativity,” are generally “Anglo- Saxon—not exactly an endangered or a tortured species, but a disposable one.” The stories are not overtly linked, as in the stories of Alice Munro where characters continuously reappear, but their tone, setting, language, and narrative arc remain relatively constant, which suggests what critic Forrest L. Ingram calls a short-story cycle—a group of stories linked to each other and balanced in their contribution to individuality and collectivity.

Each story has a climax in pathos and inspires compassion for the woe that springs from various levels and types of poverty: economic, emotional, intellectual, spiritual. The seemingly inevitable disasters are the culmination of poor choices and hapless circumstance against this impoverished backdrop. In “Pooey,” Jackie, the accident-prone, determined- to-get-pregnant, dutiful adult daughter, takes her two half-sisters on an outing to The Falls. However, her well-intentioned, but

misplaced, attention allows the infant, Lily, to fall into a vat of molten wax while Jackie tends to the teenaged Tabitha. Compared to others in the collection, these characters are lucky: they survive and inhabit the only story that ends with laughter—albeit hysterical and uncertain.

The collection’s arresting title is spoken by a walk-through character in the eponymous, first, best story. This great line represents a dismayed and frustrated plea from the variously dispossessed to a world that values them inadequately and judges them harshly. Most of Perdue’s characters mean well and would just like a little respect, please—the respect due a registered nurse. The characters are convincing, but there is a freakish, Diane Arbus quality about them; the way they fall prey to life and their own failings is unsettling. Their typical failings are anger, fear, and stupidity, often enhanced by alcoholism.

The protagonists who marry up into the middle class still carry the edge within and still suffer. Leo, the hard-working, upwardly-mobile racing-car salesman cum home-handyman of “Inheritance,” becomes “a sea urchin caught in an undertow of privilege and luxury.” He is

afraid that his “fine Italian muscle and style” may never sell another luxury vehicle, a fear that makes him permanently angry at his wife, who he thinks does nothing, his children, who are all girls, and his queer sister-in-law. He forgives his alcoholic mother-in-law because she adores him. Moreover, she has rewritten her will to give him the family’s valuable collection of vinyl recordings. Yet the narrative arc of this tale, in a bizarre exchange, take’s Leo’s paternal inheritance from him. The family dog, Shaker, vehicle of this exchange, pays the price. Leo’s anger-management training fails and he throws the little culprit into the barbeque, which, with sickening inevitability, is started by the child intended to receive the patrimony, while Leo counts to ten.

Sally Snow, the slyly named protagonist of “CA-NA-DA,” is one of the few characters who is smart and financially secure. However, she demonstrates the uselessness of intelligence without insight or selfawareness: “Her feelings, when they weren’t missing in action easily clouded her judgement.” Sally’s short in stature (an Arbus-like 4’7”), short on emotional intelligence, and, like Leo, she has a short fuse. Her brittle intellect and determination to direct her unappealing son,

Lyle, drive him to move into the basement and to forbid her to speak to him. Rather than addressing this wisely, Sally turns to Mensa, where new friends encourage her to invite a young Haitian immigrant mother, Ruth, and her baby, to share the family home. However, Sally’s unexamined guilt and anger around her son combine disastrously with her unacknowledged prejudices. After she discovers Ruth and Lyle in an intimate situation, Sally assaults the apologetic Ruth. Even then, Sally denies responsibility for her actions. Perdue conveys the unconscious nature of much Canadian racism with an apt metaphor: “Sally’d been driving in the dark. All the way home.”

Perdue is an award-winning graduate of the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies creative-writing program, and her skill is obvious. I look forward to reading much more from this new writer.

—L. Chris Fox