Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Robin Laurence

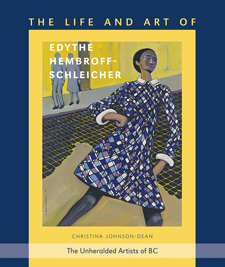

Christina Johnson-Dean, The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (Ganges: Mother Tongue, 2013). Paperbound, 168 pp., $36.95.

Within Canadian art circles, Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher is recognized as the friend, sketching companion, and memoirist of the far more famous Emily Carr. Outside that small cultural compass, she is scarcely known at all. Her obscurity as an artist in her own right is a condition that this amply illustrated biography, written by Christina Johnson-Dean and published as part of Mother Tongue’s Unheralded Artists of B.C. series, strives to redress.

Although thirty-five years younger, Hembroff-Schleicher shared some important biographical dna with Emily Carr. Both grew up in Victoria, the daughters of prosperous merchants, both longed to find more progressive forms of creative expression than their home town could offer, both travelled to San Francisco and Paris to further their art studies, and both adapted European post-Impressionism to their own creative ends. Still, the early deaths of Carr’s parents, her ensuing economic challenges, and the conservative age in which she struggled to establish herself as an artist made her journey considerably more difficult than that of her eventual protégé. Ultimately, their differences outweigh their similarities—not that either has anything to do with the mysterious chemistry of compatibility. Where Carr was a prickly outsider who appeared to relish alienating people and making herself as physically unattractive as possible (excess weight, shapeless clothes, that awful hairnet), Hembroff-Schleicher was pretty, slender, fashionably dressed, beguiling to men, and deeply attached to her family. Carr never married, Hembroff-Schleicher married three times. Carr was passionately drawn to the landscape, Hembroff-Schleicher preferred the human subject. Yet from their first meeting in 1930 until Carr’s death in 1945, they maintained a strong and mutually encouraging friendship. Early on, Hembroff-Schleicher lobbied to have an important Carr painting purchased by the provincial government, and helped organize exhibitions of her work. In her later years, she wrote two books about Carr and was named B.C.’s “Special Consultant” on its most prized artist. It seemed to irk her to take time away from her own painting to deliver Carr’s story to the world, yet she also became extremely possessive of that narrative.

Johnson-Dean, a Victoria-based teacher and art historian, has written a detailed account of Hembroff-Schleicher’s life, before, during, and after her friendship with Carr. (Late in the creation of this book, an important cache of Hembroff-Schleicher’s art, papers, and photographs was discovered in the basement of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, and it is to Johnson-Dean’s immense credit that she so fluently incorporated that material here.) The book attests to Hembroff-Schleicher’s privileged childhood, her medical problems (and their primitive treatments), and time spent, friendships nurtured, and lessons learned in the San Francisco area. Johnson-Dean’s account of her two years abroad, studying art in Paris and travelling extensively in the company of her friend and fellow artist, Marian Allardt, draws heavily from Allardt’s letters home. In addition to descriptions of their art instruction and what and where they sketched, the book details their extra-curricular activities, their shopping, sight-seeing, and party-going, the food they ate, the clothes they wore, the rooms they rented, the gifts they gave each other, the young men they dated, and their negative reactions to the avant-garde art they encountered. Curiously, only the slightest mention is made of Hembroff-Schleicher’s brief first marriage, which seems to have begun and ended in Paris.

The book records Hembroff-Schleicher’s return to Victoria and her subsequent friendship with Carr, the sketching expeditions they shared, and the advice Carr gave the younger woman, with whom she seems to have formed a jealous “maternal” relationship. Hembroff-Schleicher’s second marriage (to math professor Frederick Brand) and her subsequent moves, across the Strait of Georgia and then back and forth across Canada and to the eastern United States, are described, as are the commercial art projects she undertook, her wartime work as a translator, her postwar career as a civil servant in Ottawa, her third marriage (to her supervisor Julius Schleicher), and her return to Victoria after her retirement. Yet what remains most compelling through this carefully documented account of Hembroff-Schleicher’s life is her connection with Carr, and the books, exhibitions, and other projects she spun out of it.

It is notable that Hembroff-Schleicher once designed a book plate that declared “Application Is Genius,” since no amount of application could elevate her relentlessly mediocre talent into the realm of genius. (The bookplate homily could, however, be applied to Carr, whose creative accomplishments were hard won indeed.) The best that can be said of Hembroff-Schleicher’s paintings, prints, and drawings is that they are pleasant; the worst, that they are awkwardly composed and entirely lacking in an animating spark. Some of her most successful paintings were made from photographs she had taken of Emily Carr and her pets. Portrait of Emily Carr (with Griffon dog), 1971, captures Hembroff-Schleicher’s last visit with “a very ill Emily.” Mrs. Woo Waiting for Tea, 1934, shows Carr’s infamous monkey warming herself by an improvised camp stove. Both works are reproduced here, as are the photos they are based on.

A surprising aspect of this book, as with others in the Unheralded Artists series, is the absence of critical discussion about its subject’s art works. Some descriptions are given and conditions of creation are occasionally recorded, but there is no attempt to critically address the art. And for reasons beyond my understanding, one of Hembroff-Schleicher’s least satisfactory paintings—hell, let’s say it, most actively awful a 1968 oil titled Woman in Blue—is reproduced on the book’s cover. I can’t imagine any potential reader finding that image an enticement. Sadly, no amount of dedicated research and upbeat writing on the part of Johnson-Dean can rescue her subject’s art from the obscurity to which it has already been consigned. We will continue to remember Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher for her association with, support of, and books about Emily Carr—and really, is that such an ignoble fate?

—Robin Laurence