Reviews

Fiction Review by Candice Fertile

Horacio Castellanos Moya, Dance with Snakes, translated by Lee Paula Springer, (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2009). Paperbound, 160 pp., $17.95.

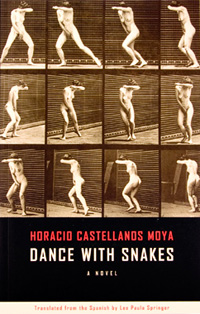

While the saying goes never to judge a book by its cover, we all know that’s nonsense as cover art is a powerful marketing device that says something about someone’s perception of the book (although often not the author’s). The staggering differences in covers between male-authored and female-authored books suggest the binary breakdown (itself problematic) rages on, pigeon-holing books in attempt to attract readers by the image on the cover rather than the words inside. So what to make of the cover of Dance with Snakes by Horacio Castellanos Moya, an American resident who was born in Honduras and raised in El Salvador? Snakes I would understand. Dancing too. But twelve small pictures of a naked woman who covers her eyes with one hand and her crotch with another? I confess that I was intrigued.

While the saying goes never to judge a book by its cover, we all know that’s nonsense as cover art is a powerful marketing device that says something about someone’s perception of the book (although often not the author’s). The staggering differences in covers between male-authored and female-authored books suggest the binary breakdown (itself problematic) rages on, pigeon-holing books in attempt to attract readers by the image on the cover rather than the words inside. So what to make of the cover of Dance with Snakes by Horacio Castellanos Moya, an American resident who was born in Honduras and raised in El Salvador? Snakes I would understand. Dancing too. But twelve small pictures of a naked woman who covers her eyes with one hand and her crotch with another? I confess that I was intrigued.

After having read the novel three times, I am no longer intrigued, just utterly mystified by the novel itself and why this cover was chosen other than for its possibly salacious effect. The book does have snakes, female talking snakes, with which the main character, a man named Eduardo Sosa, has sex. Okay, I thought, that’s kind of weird, but hey, it’s a novel, and sex with a snake is an obvious play on phallic symbols and conventions regarding intercourse. And the author is riffing on the magic realism made popular by writers such as Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel Garcia Márquez. The novel also has a huge amount of violence, much directed against women although men also are victims of Eduardo and the snakes. And some of the snakes are victims. The novel is an unabashed riot of deeply twisted imagination. It makes sense in pieces but not as a whole, and that may appeal to some readers, but I am not one of them. I can admire Castellanos Moya’s crazy wildness. Certainly there’s a movement in contemporary fiction away from plot (which has become practically vilified in some circles), but here’s another confession—I respond to plot. I respond to many other elements of fiction, but I resist being yanked around by someone’s incoherent nightmare no matter how well done it is.

Eduardo is the narrator of the first and fourth chapters while the second and third chapters have a third-person narrator who focuses on the police and then on a reporter. Eduardo is an unemployed sociology graduate who meets a vagrant living in a car. Jacinto Bustillo has run away from his wife and daughter after the loss of his job as an accountant and the murder of his lover, Aurora, whose husband is a police officer (and her killer). The four snakes are Bustillo’s companions, and after Eduardo kills Bustillo, he assumes the dead man’s identity and starts to live in the car, along with the snakes. Eduardo finds Aurora’s letters to Bustillo in the car and wants to investigate the people involved. The bodies pile up quickly as Eduardo and snakes go on a killing spree. The city is in a state of terror as the authorities scramble to find the perpetrator, believed to be Bustillo. Eduardo is thrilled by the mayhem he is causing and exhibits absolutely no remorse for any of the deaths except for that of Valentina, one of the snakes. So the world is bent out of all order. Castellanos Moya seems to be exploring the collision of various powers: public (police, politicians and media) and personal (love, sex, revenge). Add in alcohol and drugs, and it’s an incendiary brew.

The style of the novel is blunt and audacious with strong language. There is nothing beautiful or sensitive here, and those absences give it a curious punch. Certainly the novel would sound different in its original Spanish, more mellifluous given the characteristics of Spanish, and the juxtaposition of the aural and the action would contribute to a heightened sense of a world gone violently wrong. In English the flat harshness of the language simply mirrors the action, creating a different effect, perhaps equally powerful but certainly distinct. Such is the result of translation when languages have considerable sound variation. Castellanos Moya writes mostly short sentences, like the quick bites of the snakes. His use of different narrators presents various sides of the mayhem, and he is careful to show that everyone is a blend of good and evil, capable of love and hate. The emphasis is on the negative, however, and with Eduardo as the main character, the emphasis is also on the unexplainable. For example, the killing spree starts with Bustillo’s attack on a man who bites him while giving him a blow job, and then Eduardo gets in on the bloodshed: “[Bustillo] was looking through his canvas bag for an empty bottle when I took out my pocketknife, the one with the bone-coloured handle, and slit his throat.” Eduardo could simply have left. His decision to move into Bustillo’s filthy car and adopt the dead man’s identity fits his interest in sociology; nevertheless it’s far-fetched. But then, that’s the nature of the novel. Ultimately, what is one to make of all this death? Perhaps one clue lies in the fact that the car is an American one and is generally referred to that way. Maybe the novel is an allegory of interference and resulting destruction. Or maybe I am just trying too hard to make sense of it.

—Candice Fertile