Reviews

Poetry Review by Anita Lahey

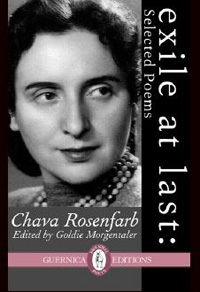

Chava Rosenfarb, Exile at Last: Selected Poems, edited by Goldie Morgentaler (Toronto: Guernica, 2013). Paperbound, 80 pp., $15.

“So if you’ve got a pillow, / bury your head in it at nightfall.” I’m seared by these lines from “Freedom,” which open the late Chava Rosenfarb’s selected poems, arranged with economy and elegance by her daughter, the scholar and translator Goldie Morgentaler. Rosenfarb composed “Freedom” as a teenager living in the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, Poland during WWII. Rosenfarb had long played at poem-making; in the ghetto, her pastime turned serious. She found a mentor in the poet Simkha-Bunim Shayevitch and became, at seventeen, the ghetto writing circle’s youngest member. She writes, “I feverishly practiced two arts at the same time, the art of writing and the art of evading deportation.” Rosenfarb had found, in her own burgeoning poetic voice, and in the defiant, literary life that thrived in the ghetto, a lifeline. She clung; she climbed. She achieved dexterity with potent tools of verse, and wielded those tools in Yiddish throughout her life, in fidelity to the language of her decimated community. It’s to her credit that she did so (she spoke five languages, after all), but it’s largely because of this choice that we, in English Canada, the country and culture in which Rosenfarb ultimately settled, have remained almost entirely ignorant of an important poetic voice.

“So if you’ve got a pillow, / bury your head in it at nightfall.” I’m seared by these lines from “Freedom,” which open the late Chava Rosenfarb’s selected poems, arranged with economy and elegance by her daughter, the scholar and translator Goldie Morgentaler. Rosenfarb composed “Freedom” as a teenager living in the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, Poland during WWII. Rosenfarb had long played at poem-making; in the ghetto, her pastime turned serious. She found a mentor in the poet Simkha-Bunim Shayevitch and became, at seventeen, the ghetto writing circle’s youngest member. She writes, “I feverishly practiced two arts at the same time, the art of writing and the art of evading deportation.” Rosenfarb had found, in her own burgeoning poetic voice, and in the defiant, literary life that thrived in the ghetto, a lifeline. She clung; she climbed. She achieved dexterity with potent tools of verse, and wielded those tools in Yiddish throughout her life, in fidelity to the language of her decimated community. It’s to her credit that she did so (she spoke five languages, after all), but it’s largely because of this choice that we, in English Canada, the country and culture in which Rosenfarb ultimately settled, have remained almost entirely ignorant of an important poetic voice.

Rosenfarb, who spent most of her post-war adult life in Canada, is known internationally as the author of The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, which won the 1979 Manger Prize, Israel’s highest award for Yiddish literature. A seminal contribution to Jewish literature of the Holocaust, the novel was unable to find an English publisher until 2004. Her poetry has fared even worse in the English-speaking world. This is unfortunate. Like The Diary of Anne Frank, long popularized as a youthful journal rather than the deliberate and accomplished work of art that it is, Rosenfarb’s ghetto poems were not mere girlhood scribblings: they belong square in the canon of Holocaust literature. Her later verse extends into its treatment of “ordinary life” the hard-won tricks she mastered early on. Her work is by turns anguished, playful, bitter, reverent, and bordering on sentimental, though she often skirts that border in order to lure her readers somewhere darker, and all too real. As a body of work, Rosenfarb’s poetry deserves a serious and appreciative audience.

The poems in Exile are arranged chronologically, as far as possible, given that her early compositions were destroyed in Auschwitz, rewritten on the ceiling above her bunk in a Nazi work camp, memorized, and finally published post-war. The three-stanza, blank verse “Freedom” is a great example of Rosenfarb’s precocious talent. She exhorts her reader to look “Far, on the other side,” to a freedom “crossed out a million times / by barbed wire.” The exaggeration makes for a visually powerful line, but Rosenfarb’s word choice is effective on a deeper level, too. Something “crossed out a million times” evokes a child at play with crayons whose game has gone too far. It’s not just that even children were trapped in the ghetto, but that even they could grasp its inhumanity. Warmth and severity vacillate throughout, echoing the tension that infected ghetto life. “Brother, take my hand. / Stop complaining.” So much is captured in this see-saw. In a state of collective suffering, people can protect or turn on one another. One must toughen up to survive. For relief, the poet suggests, bury your head in a pillow—if you have one. There’s a wrenching empathy here, bound up in full-blown rage.

Rosenfarb’s other ghetto poems reveal an ambitious writer, prying open her cultural heritage by way of her new understanding of evil. In “Isaac’s Dream,” a fictitious bride sends her bridegroom Isaac back to the “Bible’s fairytale land,” for, “I head for those places you never have dreamed of, / Where altars do smoulder with their unwilling prey.” In this poet’s world, even a boy whose own father was willing to sacrifice him is too innocent to survive. The poems Rosenfarb wrote later in life tackle faith, motherhood, love and its dissolution, the enduring mysteries of existence. With their talk of “wanton winds” and “brightest joy,” they can feel artificial or forced. It’s not hard to imagine why few found homes in contemporary literary journals. That said, most of these poems are crafted and sounded and they mean, even those with an awkward or old-fashioned ring. Some achieve a timeless power, such as “I Would Go into a Prayer House,” with its demand that God, to prove himself, must know what it is to feel “like a starving dog, / Beside himself with joy at the sight of a frozen potato.” Rosenfarb could wring every drop of potential from a metaphor, a game she played with a palpable joy. She was equally adept at restraint. Her short poem “At the Window,” about a dying relationship, echoes, in form, a nursery rhyme. That childish rhythm, embedded with sorrow, chills.

Rosenfarb thought Yiddish a beautiful, subtle language; she found English, according to her daughter and prose translation partner, Goldie Morgentaler, “cold and unemotional.” Yet she translated most of her poems herself, which might explain overwritten lines such as, “I am a grassy seaweed / that seeks you with joy to enfold.” In a phone call, Morgentaler told me many poems in Exile translate well, including the incantatory “Praise,” about the beauty of a day in which nothing happens—a marvel to a Holocaust survivor—but that others left something key behind in the Yiddish: flavour, nuance, deft wordplay. “In Yiddish she’s a very powerful writer, but she would adopt what she thought was a literary style in English that didn’t always work.” That meant, sometimes, straining for a rhyme, or choosing language Morgentaler would call “mushy.” Her mother sometimes overruled her nonetheless. Rosenfarb might have better found her “voice” in English—and more of an audience during her lifetime—had she found in Canada, as she had as a young writer in the ghetto, a literary community. But her toil, even by her own account, was solitary.

She may have preferred this. In her introduction to Exile, Rosenfarb writes, “In the ghetto, along with tuberculosis, typhus and dysentery there raged the epidemic of writing. The drive to write was as strong as the hunger for food. It subdued the hunger for food.” This sense of necessity permeated her work and never left it. Here is what may be the underlying message in Rosenfarb’s poetry: it’s in the words themselves that we live, and the only place where, in the worst of times, we might survive. Consider these, from “To a Dying Goldfish”: “How graceful, how songlike / was your harmonious sway / through the world / I have built for you. / An artificial world. / But for you it was life, / and for my eye—truth.”

—Anita Lahey