Reviews

Fiction Review by Daniel Perry

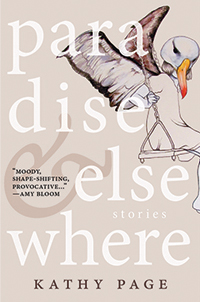

Kathy Page, Paradise & Elsewhere (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2014). Paperbound, 160 pp., $18.95.

The fourteen stories in Kathy Page’s second collection of short fiction—her first  since 1990—transport us to invented but familiar lands; from the longer first story, “G’Ming,” about a crafty beggar boy, through the three-page “My Fees,” an apostrophe in which it’s not clear who either “you” or “I” are (this reader thinks “patient” and “therapist”), the stories display a preoccupation with exchange, conversion, and translation, teasing out the distances between disparate positions while stylistically and thematically approaching the fabulous.

since 1990—transport us to invented but familiar lands; from the longer first story, “G’Ming,” about a crafty beggar boy, through the three-page “My Fees,” an apostrophe in which it’s not clear who either “you” or “I” are (this reader thinks “patient” and “therapist”), the stories display a preoccupation with exchange, conversion, and translation, teasing out the distances between disparate positions while stylistically and thematically approaching the fabulous.

At the centre of “G’Ming” lies the question about the boy’s reasons for begging and his plans for the spoils, but after successfully separating western tourists from a large sum, the boy’s grandfather reminds him that there can also be value in holding on to money. It sets the tone for the collection, asking what is truly gained by material wealth—by exchange with the affluent world—and in the next story, the much shorter “Lak-Ha,” we see a starker illustration of the theme: the mother of a family in a desert-like environment, riven with sadness to see her family failing to thrive, weeps for a week at the dining table until she dries up and dies. Her tears turn the table from wood to fibres, and the surviving husband throws these remnants away, or nearly does before a stranger passes and offers to buy them; the fibre is useful for making rope, and the family and Lak-Ha begin to profit. Over time, people begin saying the town’s name means “The place where the bargain was struck,” and to the dubious, the narrator merely shrugs (or maybe sneers): “[F]orget it. Come inside. We have everything now: television, internet, iPod, cellphone, denim jeans, Barbie doll, same as you.”

“The Ancient Siddanese” follows, and its depiction of a guide interpreting an archaeological site—and correcting the interpretation put forward by the one who discovered it years before—gives us a story that teems with conversions and translations: guide/tourist, native/foreigner, guide/archaeologist, past/present, and seeing/unseeing (for the Siddanese are all blind) are just some of the bridges that narrative needs to cross in this story. And what’s more, even the archaeologist’s account of this ancient culture’s way of life is shown to need interpretation, as it was stolen from a peer. Particularly beautiful in “The Ancient Siddanese” is Page’s imagination of the manner in which this sightless culture communicates: an alphabet entirely its own (and not, like Braille, an equivalent of a conventionally written one). It opens yet another fissure, one the Siddanese knew was reconcilable only by translation, if at all; in their public gatherings, “[T]hey sang and played instruments, they told stories, and drank an intoxicant […]. Under the influence of this drink, they became convinced that they could read the future. They saw or guessed how their own demise would come, and how the sighted world would inevitably misunderstand their achievements […]. Perhaps it’s not surprising that they wanted to build a city such as this, itself a riddle that could only be unlocked by the knowing touch of those, like them, free of the distraction of sight.”

Noting, in this story, that “the world is full of parables, prefiguration and correspondence,” the reader can see a pattern throughout the rest of the book: in “Low Tide,” a lighthouse keeper’s wife who had become a sea creature regains human form, finding that she has no memory of married life, that clothes that were supposedly hers don’t fit, and that her “husband” is much more like a captor; “Saving Grace” tells of an accomplished television news anchor’s exile to the country, where the brutish locals teach her the difference between her urban values and their rural ones; “Clients” shows us a couple paying someone to facilitate their conversation, but who can really only converse once the mediator is gone; and in “My Beautiful Wife,” a male professor realizes that his particular paradise—reading—is not solely his own when his wife begins reading more vigorously and challenges his understanding of knowledge, power, and more.

Uniting the stories’ themes of exchange, translation, and conversion with their steady attention to the natural world (and loss thereof), “We the Trees” stands among the best-achieved pieces in the collection, telling of a journalism professor’s encounter with Joshua, a strange student who is taking no courses other than hers, who never comes to class or follows assignment directions, and who decamps to the nearby forest to study a fungus said to be a network through which all the trees communicate. The mission costs the young man his life, but his final message—seemingly from the trees, through him—leaves the professor with the sudden realization that it will be her who has to convert this supernatural happening into a story the public can consume through the news media. The professor’s epiphany leads to the reader’s own, revealing the young man’s objective: to force humanity to see the destruction of the natural world from the trees’ perspective for once. The bridging of such divides in these stories can explain the collection’s title: in all cases, there is paradise, and then, an elsewhere. The conflict that arises when shaken out of the former gives these stories life—and, like the fables they resemble, profound meaning.

—Daniel Perry