Reviews

Fiction Review by Allison LaSorda

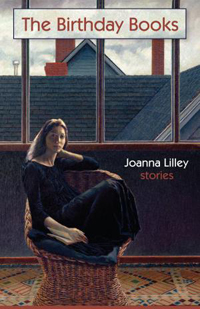

Joanna Lilley, The Birthday Books (Regina: Hagios, 2015). Paperbound, 152 pp., $18.95.

It’s immediately obvious to me that Joanna Lilley’s background is in poetry. Her concision and attention to detail mark some of the aspects she brings to her first fiction collection, The Birthday Books. Lilley is most effective with achieving a specific mood within her stories, the characters’ observations and emotional weight colouring the diverse landscapes she portrays, from Edinburgh to Whitehorse, remote Inuit communities to English gardens. Her characters lend themselves to being singled out as certain types, such as educated, British women struggling, in one way or another, to find their way—both literally and figuratively. There is a recurring unease around appearing a tourist or outsider, not wanting to be identified as such; and here, Lilley points to her characters’ insecurities or vulnerabilities, the competing impulse of being completely lost and still seeking the protective guise of knowledge. In almost every story, characters are often proving themselves to family members, lovers, or acquaintances, while navigating their circumstances through directions, maps, or detailed study of the land in which they are spending time.

It’s immediately obvious to me that Joanna Lilley’s background is in poetry. Her concision and attention to detail mark some of the aspects she brings to her first fiction collection, The Birthday Books. Lilley is most effective with achieving a specific mood within her stories, the characters’ observations and emotional weight colouring the diverse landscapes she portrays, from Edinburgh to Whitehorse, remote Inuit communities to English gardens. Her characters lend themselves to being singled out as certain types, such as educated, British women struggling, in one way or another, to find their way—both literally and figuratively. There is a recurring unease around appearing a tourist or outsider, not wanting to be identified as such; and here, Lilley points to her characters’ insecurities or vulnerabilities, the competing impulse of being completely lost and still seeking the protective guise of knowledge. In almost every story, characters are often proving themselves to family members, lovers, or acquaintances, while navigating their circumstances through directions, maps, or detailed study of the land in which they are spending time.

The exception to this may be the more dramatic, action-packed story, “Death on the Wing.” Its protagonist, Mairi searches for her absent dog in the woods late at night and finds a stranger attempting to destroy falcon eggs, presumably because the birds have been eating his pigeons. She struggles with the man before, in self defense, she pushes him off the cliffside. Panicked, she runs back to the house to find her dog dead: his throat slit. As a reader, I was left wondering the consequences of this. Mairi “doesn’t believe in an eye for an eye,” yet the thought still crosses her mind. Any culpability for her causing a man’s death seems to be alleviated by his having killed her dog. We’re left not knowing how Mairi will negotiate her future, presumably having killed someone, and the story ends without this difficult confrontation or self-reflection. Similarly, in “Travelling Light,” we follow a young woman travelling alone for the first time. Here, the narrative stops when she realizes the crisis of having lost her passport and wallet. Where does the character go from here? These situations, though frustrating, are in keeping with one of the central themes of the collection: characters are coerced or forced towards self-reflection during times of tangible external change.

A subtler subject that Lilley approaches gracefully is class. This lends itself to her representation of British characters. In “The World’s First Spin Doctor,” Rob, whose class is decided by the fact that his father is a cab driver, visits an “unemployment blackspot” in Bathgate, Scotland every summer for his holiday. Despite other evidence, Rob is certain that he’s a Viking—an identity he projects onto himself because Rob “always felt unfinished, uncertain, unclassified.” He plainly expresses a concern that preoccupies the majority of Lilley’s characters—that of feeling alienated in a familiar place. Class is also at the forefront of stories set in Yukon Territory, where some characters hunt out of necessity, and in Inuit communities, where characters draw attention to a lack of government assistance and question finding a place for art amidst daily struggles.

Lilley is clearly fascinated with the north and its people. In the story “Manniit,” she follows Jenny, a young researcher studying Inuit sculptors and their processes. Though the descriptions are elegant and interesting, the narrative feels stilted at times in that it seems to function more to disseminate information about First Nations culture than revealing the particular interiority of its characters. There is a sense of guilt, however, from Jenny as she recognizes that she only takes from this culture, and does not contribute. This is an important point the author chooses to include, and is exemplary of Lilley’s sensitivity towards her chosen subjects. This sensitivity can be found not just in terms of cultural awareness, but in her narrators’ consistent love for animals. In two different stories, having dogs inside the home or allowing dogs on the bed is referred to as “sentimental,” and yet, Lilley does not shy away from sentiment. Characters are often British women who happen to be vegetarian, and Lilley lets these idealistic characters bump up against the near-necessity of eating meat in regions where fresh produce is a luxury, which is a more understated form of culture clash.

“Perhaps Birches” is the only story in first person and, interestingly, is told from the perspective of a woman dealing with dual losses: the death of her husband and her faltering memory. At the centre of this story is the anxiety around communication, of language suddenly becoming inaccessible, even absent. As the protagonist states: “Words can be like buses. None comes for ages and then they all come at once.” Two of the woman’s daughters are members of a cult-like community from which they need permission to leave. The daughters explain, “Every decision must be a communal agreement. Autonomy is irresponsible and very destructive.” This idea, tucked away in questionable characters segregated from society, propels The Birthday Books as a whole—some individuals feel isolated, though they rarely question why, while others are adapting, creating, evolving, questioning what it means to form and participate in communities.

—Allison LaSorda