Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Madelaine Metallic

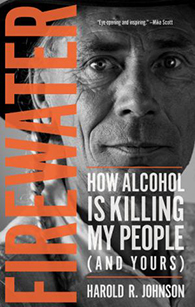

Howard R. Johnson, Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours) (Regina: University of Regina, 2016). Paperbound, 180 pp., $14.95.

Within Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours), Harold R. Johnson is on a mission to tackle the prevailing issue of alcohol abuse present in many Indigenous communities. He speaks particularly to his relatives, the Woodland Cree of the Treaty 6 territory in northern Saskatchewan, about the harmful impacts of alcohol consumption and the extremely high death rates directly connected to it. Johnson uses traditional stories, spirituality, and letters as tools to deconstruct the “Drunken Indian” stereotype.

Within Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours), Harold R. Johnson is on a mission to tackle the prevailing issue of alcohol abuse present in many Indigenous communities. He speaks particularly to his relatives, the Woodland Cree of the Treaty 6 territory in northern Saskatchewan, about the harmful impacts of alcohol consumption and the extremely high death rates directly connected to it. Johnson uses traditional stories, spirituality, and letters as tools to deconstruct the “Drunken Indian” stereotype.

Along with shining a light on this dark, difficult problem of alcoholism, Johnson encourages readers to steer away from the notion of “victimhood.” He comments on the labelling of Indigenous peoples as victims of historical trauma because, as he sees it, it diminishes their ability to redefine themselves. He encourages his readers not to succumb to the title of “victim” and challenges them to change their own story. As someone who would often blame his hardships on the fact that his dad passed away and was not there for him growing up, Johnson realized early on that he is the true determinant of his own destiny. Based on this experience, he encourages others, especially those struggling with alcohol addiction, to realize the same.

It is evident why Johnson encourages others to “change their story” and to stop self-identifying as a victim. He wants Indigenous peoples to realize that their traumatic pasts don't determine their futures. He wants to motivate his relatives and his fellow Indigenous brothers and sisters to take action against the evils of alcoholism that have taken over and destroyed many of their lives. He wants Indigenous people to change their stories for the better.

Although armed with the best intentions, his straightforward and otherwise motivational arguments can be problematic at times. For instance, when discussing what he terms “The Medical Model,” Johnson believes that, by categorizing alcoholism as a disease, the alcoholic relinquishes control, along with their responsibility to return themselves to health. He would rather refer to alcoholism as an injury, as the alcoholic would be more inclined to “nurse their injury back to health” rather than “bear the incurable disease.” Johnson's analogy could be helpful to some readers struggling with alcohol dependency, but he underestimates the compulsion intrinsic to alcoholism and, in turn, undermines those who suffer from it. For many, alcoholism is a kind of disease, an addiction nearly impossible to overcome, and a simple change of perspective will not be the solution. By viewing alcoholism as an injury, Johnson unknowingly belittles the challenges alcoholics face and, essentially, blames them for not being able to stay away from the bottle. While intending to motivate and empower victims of alcohol, Johnson instead seems to blame these people for their struggles.

As the book progresses, the author’s messages seem even more to resemble biased opinions. He claims to have based his findings on research, yet his information lacks credible sources. He also claims to be speaking solely to his relatives of the Woodland Cree yet, at times, he is addressing Indigenous peoples in general, along with the Crown Government.

In the chapter titled “Costs of the Alcohol Story,” Johnson focuses on how much the government spends to accommodate those who affiliate with alcohol. Described costs include, the amount of time police use taking care of intoxicated people (seventy-five percent of their time) and the many diseases and health issues caused by alcohol. Although some may find this information useful, I question the relevancy of this chapter.

I do not question Johnson's motives for writing this book. I admire his call to action against the addiction that is so detrimental to many Indigenous communities. I can see how Johnson's “harsh words,” as he describes them in his preface, may resonate with many people struggling with alcohol addiction. However, I worry about those who struggle with alcoholism and who, after reading Johnson’s book, will wonder why they cannot shake their “injury” as easily as others, or who beat themselves up for not wanting to quit immediately. To have broader impact, the author should have expanded the cited research and information beyond his personal beliefs and determined whether he was writing for his people only, or for everyone. Maybe then, this work would have served as a valuable and relevant resource.

—Madelaine Metallic