Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Siku Allooloo

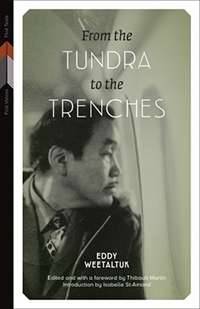

Eddy Weetatluk, From the Tundra to the Trenches (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2017). Paperbound, 210 pp., $24.95.

From the Tundra to the Trenches is a groundbreaking account of war and military life from an Inuit soldier’s perspective— the very first of its kind. In powerful and vivid prose, along with his own hand-drawn illustrations, Weetaltuk tells the story of his extraordinary life, from birth on the land, to residential school, to military combat overseas and, finally, return to a homeland drastically transformed in the time in between. Tender, honest, and often raw, Weetaltuk’s storytelling is masterful, engrossing, and deeply human. He has imbued his writing with a philosophical nuance that is characteristically Inuit: very subtle, yet profound.

From the Tundra to the Trenches is a groundbreaking account of war and military life from an Inuit soldier’s perspective— the very first of its kind. In powerful and vivid prose, along with his own hand-drawn illustrations, Weetaltuk tells the story of his extraordinary life, from birth on the land, to residential school, to military combat overseas and, finally, return to a homeland drastically transformed in the time in between. Tender, honest, and often raw, Weetaltuk’s storytelling is masterful, engrossing, and deeply human. He has imbued his writing with a philosophical nuance that is characteristically Inuit: very subtle, yet profound.

Although published more than thirty years after Weetaltuk submitted his original manuscript, From the Tundra to the Trenches has proven to be unequivocally ahead of its time. It was written by a man from a traditionally oral culture, during an era when Inuit voices were virtually absent from Canadian society as a whole. The journey of its publication is a saga in itself—a testament to the persistence and resilience of an Inuk man intent on making his mark known in a society fraught with prejudice. He wanted to ensure that young Inuit today, and the people he had encountered throughout the world, heard the story of an Inuk who managed to venture from conditions of misery to unprecedented horizons. He told it plainly in his own words, so that Inuit would recognize ourselves within this history, and be able to see the complexity of human actions, desires, faults, complications, and truths through the eyes of one of our own.

Weetaltuk knew that until his time (and that of his contemporary pioneers in Inuit literature), accounts of Inuit life had been mostly written by anthropologists as part of a greater project of colonialism. As an Inuk who had suffered and been shaped by colonial enclosure in his own territory, and who had managed to enter worlds and experiences that were both foreign and inaccessible, he recognized that his story held unique merit and resolved to ensure that it achieved the proper recognition, upheld as a top-quality publication. Weetaltuk lived a remarkable life. Although his world was structured within colonial institutions, from the newly enforced Inuit settlements and residential school to settler society and the military, Weetaltuk was driven by an uncompromising will to live as an Inuk on his own terms. How he chose to do that might come as a surprise; in order to break ground he hid his Inuit identity. Prevented from continuing his education or pursuing a future as a farmer, Weetaltuk’s experience lays bare the paradox of colonialism for Inuit of his time, who were taught to forsake our own culture and idealize white society, only to meet the harsh awakening of not being able to actually excel within it.

Growing up in poverty, with long years of famine, and witnessing his father struggle to provide in a rapidly changing world had left permanent scars. Desperate to avoid the same fate and painfully aware of his position within settler society, Weetaltuk forged a Canadian identity in order to join the military. In a moment of vulnerability, when the gravity of his decision had begun to sink in, Eddy expressed his resolve to follow through rather than desert and bring shame on his people. “If my fate was to be killed I was going to die with dignity… I was going to show the world how an Inuk fights and dies.” His assertion would ring true in a much deeper, unanticipated way: Weetaltuk’s entire life was a testament to fighting as an Inuk—against poverty and colonial oppression—and to inspire a better future for his people. Indeed, Eddy Weetaltuk, in his own way, lived, fought, and died as an Inuk.

Drawing parallels between the multiple names and numbers imposed on both himself and geographic places by colonial society (including his Eskimo tag name, E9-422), he resolved to determine his own future as a free and equal man, and pursue his dream to see the world. As Weetaltuk’s memoir makes clear, he never truly abandoned his identity; he simply turned the barriers into unlocked doors. In much the same way, Weetaltuk called on non-Inuit academics to advocate on his behalf in order to get the autobiography published, as their authority was likely to hold more weight. Thanks to his resourcefulness and the work of several collaborators, Weetaltuk succeeded in forging a place for himself and his extraordinary text in the world and, by doing so, established a cornerstone for other Inuit writers and dreamers. “I hope that young Inuit boys and girls will read about my humble life and will find in it inspiration to achieve their goals,” writes Weetaltuk. “I wish to tell them: your life belongs to you. You are the ultimate master of your destiny, so don’t let despair, alcohol or drugs control you. Be yourself, be proud. Be proud of being Inuit and always remember that our ancestors had to fight every single day of their lives to survive. It is now your turn to be strong and courageous.”

—Siku Allooloo