Reviews

Poetry Review by Jay Ruzesky

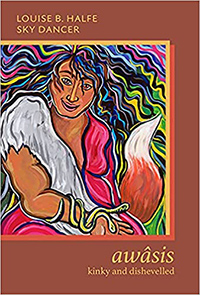

Louise B. Halfe – Sky Dancer, awâsis – kinky and dishevelled (Kingston: Brick Books, 2021). Paperbound, 86 pp., $20.

awâsis – kinky and dishevelled by Louise Bernise Halfe – Sky Dancer is a

surprising, sometimes gentle, often frank, comic exploration of a set

of “wawiyatâcimowinisa—funny little stories” (as she refers to them in

her “Acknowledgements”) collected and told by a writer who has been

for three decades at the forefront of a wave of Indigenous voices in

Canadian Literature, and who now holds the post of Canada’s Parliamentary

Poet Laureate.

awâsis – kinky and dishevelled by Louise Bernise Halfe – Sky Dancer is a

surprising, sometimes gentle, often frank, comic exploration of a set

of “wawiyatâcimowinisa—funny little stories” (as she refers to them in

her “Acknowledgements”) collected and told by a writer who has been

for three decades at the forefront of a wave of Indigenous voices in

Canadian Literature, and who now holds the post of Canada’s Parliamentary

Poet Laureate.

Maria Campbell, in her “Introduction,” says this book is “all about

Indigenizing and reconciliation among ourselves. It’s the kind of

funny, shake‐up, poking, smacking, and farting we all need while

laughing our guts out.” In a world where the media tends to highlight

the mass graves of children at Residential Schools, it is a pleasure to

have attention focused on a more rounded, rich, funny element of

Indigenous life, and, as Campbell also says, awâsis is “beautiful, gentle,

and loving” at a time when those things seem especially necessary.

Halfe – Sky Dancer is a Cree poet who was taken to Residential

School as a child and raised there until she was sixteen. Her 2016 book,

Burning in This Midnight Dream, reviewed in The Malahat Review 197

(Winter 2016), tells stories of Residential School survivors including

her “Dedication to the Seventh Generation,” which incites readers to

weep “for those who haven’t yet sung” and those “who will never

sing.” But her latest collection is something else: an ameliorative

chorus of voices this time “celebrating awâsis, the adult child within.”

Halfe is a gentle teacher. She explains that “awâsis means more than

child. It translates to ‘being lent a spiritual being.’ awâsis celebrates and

helps us to laugh at ourselves and our follies.”

While readers are encouraged to laugh, there are also lessons here

and they are offered in a generous way. One of the things the book

explores is language, both English and nêhiyawêwin. The first time

Halfe uses a Cree word like nêhiyaw, for example, she provides an

English translation in the margin so we (by which I mean “we who do

not already know”) learn the word for Cree, and we learn that kêhtêayak is old ones/old people and kôhkom is Grandma.

“English is Not the First Word” pokes at language in a seriously

playful way that reminds me of some of the puns bpNichol was fond

of—turning language on its head so we can take a closer look at it. In

this poem, awâsis mixes up words, as when she goes to get her “claws

pet‐dee‐cured / at a high‐end sell‐on.” She goes in and the beautician

tells her to “shit down.” These lines are at once a kind of scatological

humour that grade‐school kids find hilarious and part of a sensibility that isn’t afraid of what the body does and can critique the cultural

role of a “sell‐on” with a sharp phrase. In the next stanza, she talks to

a “crowd of engine‐ears” in “her broken England,” gently hinting that

the problems of communication might have much to do with the

dominant language imposing itself.

Some of these funny little stories are just that: knee‐slappers, oneliners,

or puns so punny that they groan for us. “Indian Botox,” for

example, describes how “awâsis was feeling her years” and used some

Preparation H to “tighten the creases.” Then Little Whiteman (a character

who appears throughout the book) wonders why awâsis is

“smearing / that butt cream on?” Her answer is “So my face could be

as tight / as your ass.” Tomson Highway has talked about the way that

in Cree laughter and bodily functions often go together, so this poem

provides that sort of chuckle in its punch line. Another poem, “Hospital

Stay,” begins with a similar sensibility. We are told that awâsis is

in the hospital when a nurse walks in on her friend giving her a back

rub. The nurse asks what is happening and she says, “We’re having

sex, want to join us?” The poem takes a turn when the nurse cannot

seem to bear the humour of “her nêhiyaw” friends. The response is

much different than the punchline in the previous poem; awâsis offers

to give the nurse lessons in laughter and is told she should be asleep,

but awâsis was told “when to go to bed in residential school,” and says,

“Now I am seventy‐five. I think I can decide when I should sleep.” In

this case the “joke” has a very different gravity.

Near the centre of the collection is a poem called “Enlightenment,”

which seems a sort of exemplar of the whole project. The poem introduces

a character called “Falls Down” who enters with a “thunder

cloud following” and asks awâsis for help removing “the dark clouds

that dwelled in / the shadowed walls of her lodge.” With the help of a

flannel bedsheet and some owl broth, “awâsis unbraided a cobweb of

tiny bones, / bunched grass, and bitter herbs / that Falls Down had

swallowed.” This tonic, like the “Love Medsin” of the book, has the

desired effect; Falls Down lets loose and “laughter rumbled up / and

released the clenched darkness. // And gave Falls Down joy.” Halfe

does not shy away from the black cloud of colonial history, but she is

aware of the brightness and humour that can help heal.

—Jay Ruzesky