The Malahat Review: A Brief History

of its Early Internationalism

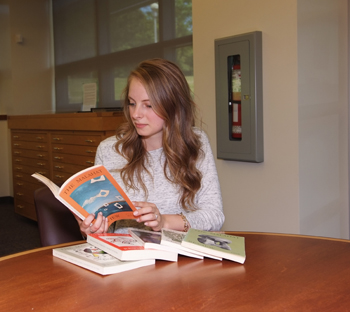

Karyn Wisselink is working towards a Combined Major in French and English Canadian Literature at the University of Victoria. She worked as editorial assistant for The Malahat Review from 2013-2014, and is currently an editorial assistant at Victorian Review. Her interest in Canadian literature and the world of publishing prompted her to write this essay for a modern Canadian poetry class with Nicholas Bradley at the University of Victoria. The research for this essay involved countless hours in Special Collections where Robin Skelton’s papers are housed. The papers range from postcards, to scraps of papers, to carbon copies of letters, to newspaper clippings. Assisted by Skelton’s memoirs and back issues of The Malahat Review, this essay came together to reflect not only its history, but also Skelton’s life and philosophy.

Literary journals provide some of the best reflections of a literary landscape at certain points in time; they capture the wide range of literature available by publishing various genres written by emerging and well-established writers. In Canada, literary journals were highly regarded and received praise in The Massey Report (1951), which concluded that “in our periodical press we have our closest approximation to a national literature” (Massey 64). These early journals documented the trends and the writers who were influencing Canadian culture. However, circulation was mostly contained within Canada and there were few journals in Canada that supported writers on an international level. In 1966, Robin Skelton and his colleague John Peter began planning The Malahat Review, a journal intended to benefit the Canadian literary landscape with an international and even cosmopolitan approach. Although Skelton and Peter would be criticized for their global perspective, The Malahat Review promoted a cosmopolitan view of literature and language. By highlighting the variety in international literature, The Malahat Review provided an awareness of other cultures, which was intended to help define what it meant to be a Canadian writer.

The philosophies on which The Malahat Review operated were largely influenced by Robin Skelton. Skelton was born in Yorkshire in 1925. He studied economics, civics, and politics at Cambridge University and English literature at Leeds University. He began his teaching career at the University of Manchester in 1951. In 1963, Skelton crossed the ocean to teach at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, before accepting a position at the University of Victoria where opportunities to “start things,” as Skelton says, abounded (Memoirs 180). Among other things, Skelton initiated the Special Collections wing of the library at the University of Victoria, founded the Department of Creative Writing (now the Department of Writing) and, established The Malahat Review. The idea for The Malahat Review began in a conversation with John Peter about “the state of Canadian letters, and mourning that there was no Canadian literary journal of international standing” (Memoirs 204–5). As writers themselves who were not from Canada, Skelton and Peter understood the necessity of an international stage in literature. Skelton became the face of the journal and it was Skelton, not Peter, who participated in newspaper interviews. John Peter had only planned to edit the journal for five years and resigned in 1971. Skelton took over as sole editor and his cosmopolitan philosophies continued to shape the journal until 1983, when he stepped down.

Skelton and Peter’s meticulous planning and carefully curated first issue determined the direction of their subsequent issues. The title of any magazine is crucial, acting not only as an introduction but also as something that will fix itself in a reader’s memory. The Malahat Review was originally entitled the Camosun Quarterly, “A Magazine of the Humanities” but it was changed to The Malahat Review with the subtitle, “An International Magazine of Life and Letters.” The title, also the name of a mountain pass north of Victoria, was carefully selected to represent the region where it was published and was intentionally “meaningless and carried no implications of the journal’s contents or attitudes” (Memoirs 205)—in that to readers unfamiliar with the aboriginal language from which it is drawn, “Malahat” would not influence  how they viewed the journal’s contents. However, the choice of “Malahat” by today’s standards will be seen to reflect the 1960s’ cavalier grasp of First Nations culture and by many as an unthinking appropriation of aboriginal language. Skelton’s cosmopolitan philosophy required that the title should not limit what could be published. Other journals, such as Canadian Literature which is inward-looking and Prism International which looks outwardly, were restricted by their titles, limiting them to the publication of only Canadian literature or international literature, respectively. Skelton resisted the idea of limitation. In a letter to Jonathan Williams in Florida, he suggests the broad scope of the journal by asking for “translations from almost every language, and for literary memoirs, collections of letters, and autobiographical excursions” (Letter to Williams). However, Skelton did try and limit his focus to certain areas of the globe, such as South and Central America because “currently much attention is being paid to Africa” and “the Far East has also received much attention recently” (“Proposed Scope”). This focus was more of a marketing technique, allowing the journal to fill a niche market.

how they viewed the journal’s contents. However, the choice of “Malahat” by today’s standards will be seen to reflect the 1960s’ cavalier grasp of First Nations culture and by many as an unthinking appropriation of aboriginal language. Skelton’s cosmopolitan philosophy required that the title should not limit what could be published. Other journals, such as Canadian Literature which is inward-looking and Prism International which looks outwardly, were restricted by their titles, limiting them to the publication of only Canadian literature or international literature, respectively. Skelton resisted the idea of limitation. In a letter to Jonathan Williams in Florida, he suggests the broad scope of the journal by asking for “translations from almost every language, and for literary memoirs, collections of letters, and autobiographical excursions” (Letter to Williams). However, Skelton did try and limit his focus to certain areas of the globe, such as South and Central America because “currently much attention is being paid to Africa” and “the Far East has also received much attention recently” (“Proposed Scope”). This focus was more of a marketing technique, allowing the journal to fill a niche market.

In order to create the first issue, Skelton himself sought out writers who would set the precedent for what could be expected in the following issues. Skelton retained this active editorial position, believing that “the only way is to go out and find material, because the best material always has to be found” (Thomas 24). Much of Skelton’s correspondence prior to publication of the first issue was to ambassadors of foreign countries or writers in a wide range of countries including Chile, Brazil and New Zealand. These letters solicited submissions and requested contact information for writers in these countries. In a document entitled “Proposed Scope and Character of the Magazine,” Skelton argues that “no adult quarterly can nowadays affords to neglect the international scene,” (“Proposed Scope”) implying that Skelton’s internationalism was not only a philosophy, but also a necessity to the increasingly globalized scope of literature. Earle Birney, the editor of Prism International, agrees with the necessity of a world literature and states in an editorial comment that “we do not believe, in the world of 1964, that explanations need to be made for thinking that internationalism is a paramount consideration” (5). The phenomenon of globalization, which was rapidly spilling over from trade into culture, was becoming a convention of modern life.

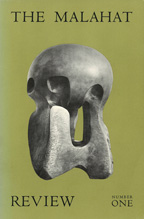

After a year of planning, The Malahat Review’s first issue appeared on January 1,  1967, coinciding with the beginning of Canada’s centennial year. The year may have been coincidental but Skelton reported to The Martlet, the university’s student newspaper, that “Canada can make a worthwhile contribution in life and letters during its hundredth year” (5). Despite this statement, the first issue of The Malahat Review contained more writers from England than from Canada; there were only two Canadian writers printed in this first issue. The low representation of Canadian writers, Skelton argued, could be attributed to the fact that “at first, very little Canadian material of merit landed on our desk” (Memoirs 224). Later issues of The Malahat Review would include more Canadian authors and Skelton would even dedicate entire issues to Canadian writers and artists. However, the first issues would result in criticism of The Malahat Review for not supporting Canadian writing.

1967, coinciding with the beginning of Canada’s centennial year. The year may have been coincidental but Skelton reported to The Martlet, the university’s student newspaper, that “Canada can make a worthwhile contribution in life and letters during its hundredth year” (5). Despite this statement, the first issue of The Malahat Review contained more writers from England than from Canada; there were only two Canadian writers printed in this first issue. The low representation of Canadian writers, Skelton argued, could be attributed to the fact that “at first, very little Canadian material of merit landed on our desk” (Memoirs 224). Later issues of The Malahat Review would include more Canadian authors and Skelton would even dedicate entire issues to Canadian writers and artists. However, the first issues would result in criticism of The Malahat Review for not supporting Canadian writing.

In the first issue, Skelton collected writers from around the world to contribute to a group of poems entitled “An Atlas of Poetry,” a feature that would reappear in subsequent issues. The themes of the poems are as various as the countries they come from. Although they form an atlas, the poems are not specifically about place. The atlas begins in the same country where Skelton’s life began: England. The atlas then traipses through Eire (or Ireland), the U.S.A back to England, to the Philippines, Germany and finally ends in Pakistan. The rest of the issue is filled with essays, dramas, short stories, previously unpublished letters from D.H. Lawrence, and worksheets, which visually follow a poem through drafts to its final form. Although the first issue feels rather European, Skelton would continue to strive toward “a general widening of the imaginative range of literature” (Issue 21, 8). His  later issues of The Malahat Review contain Canadian writers of note such as Irving Layton and George Woodcock and also reach beyond European contributors to writers in every corner of the world. For Skelton, literature was always intended to be broad and limitless. Skelton saw literature as the most effective way of bringing the world closer together in a cosmopolitan sense.

later issues of The Malahat Review contain Canadian writers of note such as Irving Layton and George Woodcock and also reach beyond European contributors to writers in every corner of the world. For Skelton, literature was always intended to be broad and limitless. Skelton saw literature as the most effective way of bringing the world closer together in a cosmopolitan sense.

George Woodcock, the founder of the nationalist literary journal, Canadian Literature, found Skelton’s internationalism appealing. Looking back at The Malahat Review’s beginnings, Woodcock felt that “by ‘international’ Skelton and Peter meant something even more cosmopolitan” (50). Skelton’s editorial comment in Issue 40 reminds his readers that “in this global village, we have not one but many neighbours” (8). He urges his readers and critics to look beyond the borders of Canada to “learn from all those neighbours” (8). By broadening the scope of The Malahat Review, Skelton made these global neighbours more accessible and literature became the point of access. Woodcock argues Skelton’s philosophy was that “whatever our language, so long as we use it with skill and respect, we belong to one another” (Woodcock 53). This cosmopolitan view is echoed in the numerous translations found in The Malahat Review, such as “Grandmother,” a poem featured in the first issue’s “Atlas of Poetry.” “Grandmother” was written by Rolando S. Tinio (from the Philippines) and translated from the Tagalog, an Austronesian language, by Bienvenido Lumbera. The sharing of literature across language barriers was an important part of Skelton’s borderless philosophy.

Through his cosmopolitan understanding of literature, Skelton believed that he could remove linguistic barriers and thematic limitations from his journal. The Malahat Review would educate readers and “in discovering differences come to a  better understanding of what is, for them, uniquely Canadian” (Issue 40, 8). The Malahat Review was published not only for the purpose of publishing writers, but also for the purpose of reading. Skelton’s international selections would allow readers to understand the global influence of literature and find an understanding of their own literature through a cosmopolitan perspective.

better understanding of what is, for them, uniquely Canadian” (Issue 40, 8). The Malahat Review was published not only for the purpose of publishing writers, but also for the purpose of reading. Skelton’s international selections would allow readers to understand the global influence of literature and find an understanding of their own literature through a cosmopolitan perspective.

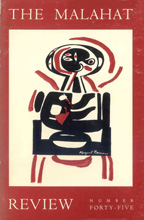

Skelton believed that imposing the label of Canadian literature was not only limiting, but also arrogant. On a scrap of paper, Skelton scribbled ““We therefore, reject chauvinistic notions of supporting only the literature of our own country” (Scrap), indicating the impossibility of a national focus in the periodical world. However, Skelton’s strong opinions against the idea of giving special treatment to Canadian writers do not imply that Skelton did not support Canadian writing. Skelton claims that he “believed in Canada’s cultural and literary strength more firmly then a good many Canadian Nationalists” (Memoirs 228). The fact that Skelton’s nationalism was implicit in his cosmopolitan approach was lost on many critics, especially as Skelton set The Malahat Review above other Canadian journals. The Daily Colonist reports Skelton saying that The Malahat Review “should not be equated with ‘little journals’ which are intended to foster purely Canadian writers” (24). Although “little journals” is a term used to distinguish literary journals from commercial magazines, the adjective “little” carries a negative connotation in Skelton’s quote and implies that The Malahat Review is “bigger” because of its international reach.

Despite the criticism of Skelton’s agenda for The Malahat Review, Skelton became increasingly concerned with Canadian literature. George Woodcock argues that although The Malahat Review’s success stemmed from an international outlook, the true triumph was that the journal was also “national and strongly regional” (52). In the planning stages of The Malahat Review, Skelton argues that, “while the Editorial Policy should be rather international than nationalistic, there is a great need for work in the field of Canadian Bibliography” (“Proposed Scope”). Rather than bias editorial decisions on nationality, Skelton’s idea was publish “authoritative checklists” of prominent Canadian writers, and also to “commission survey-articles on some aspect of Canadian Arts and Letters” (“Proposed Scope”). Beyond this, Skelton would give no special treatment to Canadian writers. However, Skelton’s global philosophy was also inherently national as The Malahat Review “introduced the work of Canadian writers to a world-wide audience” (Memoirs 225) and also proved that Canadian literature “could stand up to competition from anywhere” (Memoirs 228). The Malahat Review was fostering Canadian writers in an international context. The differences between literatures would help define what set Canadian writers apart from writers in other nations.

Skelton would eventually dedicate entire issues to Canadian literature. Most notably,  in January of 1978, The Malahat Review published a hefty special issue called “West Coast Renaissance.” The double-length journal was made possible through funding from the Canada Council and the British Columbia Cultural Fund. Many of the writers included in this issue, including Marilyn Bowering, Patrick Lane and Susan Musgrave, had been previously featured in The Malahat Review, proving that Skelton was committed to publishing Canada’s best writers alongside their Canadian and international contemporaries. However, previous to this issue, Skelton notes in Issue 31 that “after having been accused, in

in January of 1978, The Malahat Review published a hefty special issue called “West Coast Renaissance.” The double-length journal was made possible through funding from the Canada Council and the British Columbia Cultural Fund. Many of the writers included in this issue, including Marilyn Bowering, Patrick Lane and Susan Musgrave, had been previously featured in The Malahat Review, proving that Skelton was committed to publishing Canada’s best writers alongside their Canadian and international contemporaries. However, previous to this issue, Skelton notes in Issue 31 that “after having been accused, in  our early days, of denying Canadian writers opportunities by issuing a journal which published work by non-Canadians, we were then criticized for placing Canadians in a sort of literary ghetto” (5). This literary ghetto was what Skelton planned to avoid by creating a journal with a worldwide perspective. Skelton believed that Canadian culture had a tendency to be dominated by “narrow notion[s] of what constitutes the ‘Canadian Experience’” (Issue 40, 7). The label “Canadian literature” immediately applies a set of expectations on the work and limits the reader’s interpretation. “International,” which connotes few limitations, became a synonym for Skelton’s cosmopolitan philosophy.

our early days, of denying Canadian writers opportunities by issuing a journal which published work by non-Canadians, we were then criticized for placing Canadians in a sort of literary ghetto” (5). This literary ghetto was what Skelton planned to avoid by creating a journal with a worldwide perspective. Skelton believed that Canadian culture had a tendency to be dominated by “narrow notion[s] of what constitutes the ‘Canadian Experience’” (Issue 40, 7). The label “Canadian literature” immediately applies a set of expectations on the work and limits the reader’s interpretation. “International,” which connotes few limitations, became a synonym for Skelton’s cosmopolitan philosophy.

The subtitle “An International Magazine of Life and Letters” was dropped from the journal’s title after Skelton resigned his position as editor. The journal would now direct its attention more fully on Canadian literature, once again proving that few people at the time agreed with Skelton’s international approach. The Malahat Review is successfully published today with a continued focus on Canadian literature. Skelton’s cosmopolitan philosophies were crucial to the foundation of the journal, however the literary landscape is constantly in flux and as a representative of this landscape, a journal must be able to adapt in order to survive. Robin Skelton introduced The Malahat Review and the city of Victoria to the international world of literature. His cosmopolitan ideas were international in nature; however, through the differences portrayed in The Malahat Review, Skelton believed he could prove the capabilities of Canadian writers and help define the Canadian identity. The success of The Malahat Review at its beginnings and continuing today is a testament to the strength of a national literature.

Works Cited

Birney, Earle. “Editorial.” Prism International 4.1 (1964): 3–5. Print.

Massey, Vincent. Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences 1949–1951. Library and Archives Canada. The Government of Canada. 21 Jan 2001. Web. 28 Mar 2014.

Peter, John and Robin, Skelton. “Proposed Scope and Character of the Magazine.” 1971–1, Box 14, File 8. SC114 Robin Skelton fonds. The University of Victoria Special Collections, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria. Print. 6 Mar 2014.

Skelton, Robin. “Comment.” The Malahat Review 21 (1972): 5–7. Print.

Skelton, Robin. “Comment.” The Malahat Review 31 (1974): 5–7. Print.

Skelton, Robin. “Comment.” The Malahat Review 40 (1976): 5–8. Print.

Skelton, Robin. Memoirs of a Literary Blockhead. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1988. Print.

Skelton, Robin. Letter to Jonathan Williams. 5 October 1965. 1981–26, Box 13, File 24. SC114 Robin Skelton fonds. The University of Victoria Special Collections, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria. Print. 6 Mar 2014.

Skelton, Robin. Scrap paper. 1971–1, Box 14, File 8. SC114 Robin Skelton fonds. The University of Victoria Special Collections, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria. Print. 6 Mar 2014.

Thomas, Bill. “The Malahat Review.” The Daily Colonist [Victoria]. 9 April 1972. 24. Print.

“UVic’s Mighty-mite Literary Quarterly.” The Martlet [Victoria]. 3 Nov 1966. 5. Print.

Woodcock, George. “Admirable Eclecticism.” Skelton at 60. Erin: Porcupine’s Quill, 1986. Print.