From Model Ts to Motorcycles:

The Auto - History of the Lapointe/Katchur family

by: Steve Katchur

March 19, 2009

“It gave us a lot of freedom,” was my grandma, Rose Lapointe’s response when I asked her about the impact that the automobile had on her family’s life.1 Her reaction is representative of the rural Saskatchewan she grew up in, where, until the advent of the automobile, most farming towns remained isolated from the rest of the world. Similarly, historian L. J. K. Setright proclaims that “[t]hroughout its history the car has been a liberator . . . the car has enabled people to break out of their constraints . . . to venture somewhere they could never previously go.”2 Nowhere was this liberation more true than in the Saskatchewan of the twentieth century. As the province motorized, the car played an ever-increasing role in day to day life and connected friends and family across the province and the country.

This paper will explore how the automobile impacted the lives of my family, who, with the exception of my step-father, grew up in Saskatchewan. Beginning in the 1920s with the lives of my Grandparents, Julia Katchur (Nee Bilinski), Charlie Lapointe and Rose Lapointe (Nee Shanner), and finishing with the marriage of my mother and step-father, Carol Lapointe and Rod Wood, the personal experiences and histories of my family paint a personal picture of many of the major changes that the automobile brought for Canadians in the twentieth century.

Saskatchewan, the Early Years: My Grandparents

The first generation of car owners in Saskatchewan was made up mostly of farmers. During the ‘roaring Twenties’ - a nickname based on the mass-mobilization of North American society - many Canadians were able to purchase their first cars. Whether it was the ever-popular Model T, or one of a number of other makes, the automobile brought both economic and social improvements to many rural families on the Prairies.3 Yet, as we shall see, the car was both a blessing and a curse, and not every family in Saskatchewan experienced the automobile in the same way.

Julia Bilinski was born in 1926 on a family farm eleven miles outside Punnichy, Saskatchewan. Although, at this time, cars were a common sight in the province, the Bilinskis, like many farming families, were still dependent on animal and manual labour.4 By 1927, however, a new phenomenon was hitting the car market: first-time buyers made up less than half of all new car purchases. As a result, Ford’s domination of the low-end market now had to compete with an influx of secondhand cars. For less money than a Model T, one could now purchase a used car that offered a smoother ride and more features, such as a self-starter or de- mountable rims.5 By 1938, when Julia’s family purchased their first car, they went straight to the second-hand market, buying a 1926 Essex. 6

Automobiles made the lives of prairie families, such as the Bilinskis, easier and more mobile. Farmers used their cars for taking product to local markets, getting farm supplies, and traveling to see family. So helpful was the automobile to such families that it was soon viewed as a farmer’s necessity.7 More than a tool for work, however, the automobile also provided an escape from farming life and a freedom of mobility unknown to previous generations. Before motorization, rural Saskatchewan was often cut-off from the outside world. As was the case for Julia’s family, many farmers lived miles away from the nearest rail link and no bus system was offered.8 The automobile was able to overcome great distances that previously seemed too far to travel, turning a group of isolated farms into a community.9 Julia remembers that “as a family, we would always get in the car and go some place;” whether it was traveling into Punnichy to get supplies or visiting family in different parts of the province, places which used to be unreachable, were now all within an hour’s drive.10

Charlie Lapointe was born to a farming family in Rosetown, Saskatchewan in 1933, and at the time, his father Omer, proudly owned a 1926 Ford Model T.11 It was the perfect car for the Prairies. Built by Henry Ford, a farm boy himself, the Model T was durable and reliable on the vastly unpaved terrain of the Canadian West.12 Yet, this vehicle was a symbol of more affluent times, for by 1933 the Prairies were in the middle of a two-fold disaster: economic depression had struck the Western World, and drought had hit the prairies. From 1930-1936, a period known as the ‘Dirty Thirties’, many farmers were unable to grow crops and, as a result, they became dependent on government work projects and handouts to survive. 13

Faced with economic ruin, many Canadians packed up all their belongings and, in the words of Premier Tommy Douglas, “walked away from a lifetime of work and a whole lifetime of hopes and dreams unrealized.”14 In 1937, with nothing left for them in Rosetown, the Lapointe family moved to Macdowall, Saskatchewan to rent some land; Charlie was four. Unfortunately, farming in Macdowall was not very productive, and the family had to start a wood-cutting business to help pay the bills. In such a climate of economic uncertainty, Omer could no longer bear the expense of the Ford.15

Cars were no longer affordable for many families across the country who were out of work and low on savings. In the Thirties, the price of gas was cheap, but it was still more than the poorest drivers could afford. Even farmers who had produce to sell, suffered from atypically low prices; grain, poultry, and red meats were all selling at a fraction of their worth.16 With little or no income, many families opted to sell their cars, but the market was not favourable. Low demand, and an abnormally high supply of used automobiles, forced people to sell their cars for well below their value.17 Such was the case for Omer who, in Charlie’s words, “sold the car for peanuts.” Their car sold for only twenty dollars.18

At the end of the decade, Canada entered the Second World War and the push for wartime production helped strengthen the country’s economy. But if this economic shift was noticeable in urban centres, for many on the Prairies, things were slow to improve. As Charlie recalls, the “Thirties went into the Forties for us.”19 In some parts of the province, the drought lasted until 1940, and even after that, the hards times persisted. Automobiles remained out of reach for much of the rural poor, and with few rail-links and no buses, many people remained isolated in their poverty.20 By 1948, with nothing to stay home for, Charlie, aged 15, left Macdowall to look for work.21

Back in Rosetown, which was recovering from the ‘Dirty Thirties’ much faster than Macdowall, Charlie was hired as a farm labourer, and he soon money had enough to buy his first car, a 1926 Star. Charlie was excited about the social implication of owning one. “You were a pretty popular guy if you had a car. Anyone who could get a car could get a girlfriend,” he recalls.22 Indeed, for many Canadians, the car provided a new place for romantic endeavors, and for more liberal couples, the car was a prime location for sexual interludes. Courting, which used to take place on the front porch, could now be done in the private space of the automobile, or in any private place to which one wished to travel. 23 Still, a date in Charlie’s Star was not all romance; the car’s vacuum tank would sometimes lose its prime and Charlie would have to siphon gas to put back into the tank. “Girls didn’t like kissing gassy lips very much” he chuckles.24

In 1938, Rose Shanner was born on a farm just outside of Estevan, Saskatchewan. Born after the ‘Dirty Thirties’, her earliest memories of the automobile was her family’s 1935 Dodge truck.25 Like with Julia’s family car, the Dodge provided the Shanners with a social and economic lifeline, enabling them to make frequent visits to Estevan for shopping, for fun, or to visit family. Yet, the improvements that the automobile brought were only seasonal, as the cars of the day were no match for Saskatchewan’s winter conditions. Horses were a more reliable form of transportation in the winter months: they could withstand extremely cold weather, and were able to travel over muddy and snow-cover roads which would have otherwise constituted extremely poor driving conditions. “Nobody ever drove in the winter,” she remembers; as soon as snow fell, she and her friends relied on a horse-drawn sleigh to get to and from school. The only way to get to Estevan was through a generous neighbor, Mr. Wingert, who took people into town on his Bombardier snowmobile.26

If the automobile’s seasonal limitations were an inconvenience, motor-crashes were a much more somber drawback of the motorization of Canadian society; as the number of motor- vehicles on the road increased, so too, did the number of motor-accidents. From 1921 to 1929 the annual number of fatal motor-vehicle accidents in Canada rose from 197 to 1300, a number which rose to 5000 per year by the 1960s.27 One such accident deeply affected the Shanner family. Rose’s Uncle Leon, who had survived fighting in the Second World War, ironically died in a motor accident shortly after arriving home to Saskatchewan. In addition to mobility and freedom, automobiles also brought inherent risks.

Interestingly, some of the social impacts of the automobile in the Prairies differed from other parts of the country. Much of rural Saskatchewan did not experience the loosening of traditional gender modes experienced in many of North America’s urban centres, where, by the 1920s, urban women were spending an average of seven and a half hours a week behind the wheel.28 In many farming families, driving was still viewed as part of the man’s domain. Although, Rose’s mother, Anna - like many farmer’s wives - did drive trucks around on the farm, away form their home and in the public gaze, Ralph, Rose’s father, always drove the Dodge. As a result, Anna did not need to get a drivers license until after Ralph passed away. Consequently, Rose had no desire to get her license until after she married Charlie.29

The Happy Couples: Julia and Peter, Charlie and Rose

As Canada’s love affair with the car continued, it influenced society and environment in new and significant ways. Better cars, along with more extensive highway systems, enabled many Canadians to vacation further from home than ever before. Women were also overcoming gender stereotypes associated with the car, as moms and wives behind the wheel became a more common sight. Moreover, as increased motorization created an assortment of new industrial jobs, car-friendly infrastructure made driving-related careers one of the fastest growing sectors in the country’s job market. Ever-popular, and unchallenged, the automobile was in its ‘Golden Age’.30

In 1943, Julia met Peter Katchur, and a year later, they got married and moved to Wilsonville, Ontario. After a brief time labouring at a tobacco farm, Peter took a job at the Massey Harris Shop in Branford, which produced machinery, and parts for tractors and other farm equipment.31 The emergence of Taylorism and Fordism enabled many industries to de-skill their workforce, allowing Peter to obtain this well-paying low-skilled job.32 Peter and Julia had soon saved enough to buy their first car, a 1935 Chevrolet. Not only did their car make Peter’s twelve mile commute to Branford more convenient, like Saskatchewan’s first generation of car owners, the Chevrolet enhanced Julia and Peter’s social lives. Over the years Julia remembers taking many trips to the beach, and driving to friend’s houses on weekends for parties and dinners.

When the time came to move back to Saskatchewan in 1949, Peter traded the car in for a panel truck, and the family was able to drive across country, a luxury they could not afford when they moved to Ontario six years earlier. The truck enabled Julia’s family to bring more of their belongings, and served very useful in Peter’s future job in waterworks. Eventually, Peter and Julia found their way to Regina in 1954, where my father, Mike Katchur was born in 1958.33

Charlie met Rose in 1954 after moving to Estevan to find work; two years later, they married. Although they did not own a car at the time, by 1958, they purchased a 1955 Buick from Rose’s parents. On Charlie’s insistence, Rose got her drivers license, and the car opened up a world of opportunities. “It gave us both a lot of freedom,” Rose recalls. “It made it so Grandpa didn’t have to do everything.” Indeed, the era of the family car had arrived. As the vision of the nuclear family came to the forefront of Canadian culture, roomy cars that were easy to drive became popular. Women drivers of the 1950s and 1960s were not the independent working women of the previous generation, but house-wives running errands.34 As women behind the wheel became more acceptable, Rose was able drive around town for groceries, family visits, or to take their kids to sports practice and other activities. 35

If the gender roles surrounding the automobile and its drivers were changing, its role as a status symbol was not. By the 1950s, despite Henry Ford’s efforts to build a classless car market, automobiles had become a visible a symbol of one’s class.36 Such distinctions between car buyers, was capitalized upon by companies such as General Motors who released multiple lines of cars to reach every level of the market. If one had a modest budget, one could purchase a Chevrolet. With more money one could buy a Buick or even a Cadillac, and the people who owned the Buicks or the Cadillacs, loved to show them off.37 Although Estevan was small enough to walk everywhere, people drove at every opportunity. “Owning a nice car like a Buick was a showpiece,” remembers Charlie, “and farmers in Estevan who had money wanted to show it.”38

The Buick also gave Charlie and Rose the ability to go on vacations outside the province and the country. Charlie recalls that, when he was growing up, Omer always joked about going to California. In 1960, Charlie made that joke a reality, planning to take his family and parents to the ‘Golden State’. “When I first told him that we were going, he laughed at me,” but soon the camping gear was packed, and they headed off.39 Such a trip was made possible through the massive highway and interstate projects undertaken by Canada and the United States after the Second World War. Thousands of miles of new highway enabled many families to embark on similar road trips throughout the country. By the end of the Fifties, it seemed that every Canadian had a road-trip story to tell.40 Traveling for twenty-days, the Lapointes camped and cooked their way through the Canadian and American Wests, setting up their tent in campgrounds, forests, graveyards, alfalfa fields, or anywhere they could find. It was the trip of a lifetime.41

More than convenience or pleasure, the motorization of Saskatchewan provided Charlie with many employment opportunities. Looking back over his life, Charlie recalls that “it was the car that made my living.”42 Indeed it was Charlie’s willingness to be behind the wheel that enabled him to provide for his family. Without a formal education, Charlie had fewer job options, but he did not mind driving, an attitude which served him in many jobs. Over the years, Charlie drove trucks for Esso, drove on the oil rigs, drove a service vehicle for Coca-Cola, worked in sales with Bowes Company, and eventually became a traveling Salesman for Robin Hood in 1976. Working sales out of Regina, Charlie drove over 100 000 km per year until his retirement in 1997. Until recently, Charlie still drove a lot, seeing all fifty United States with his wife, and traveling great distances to visit his family who has spread out throughout Canada.43

The Next Generation: Rod Wood and Carol Lapointe

After over a generation of automobile lovers, society began to develop mixed feelings about cars. Concerns about the environment and safety, as well as the impact of the oil crisis of 1973, led to a public uncertainty about the role that automobiles were playing in society. A new generation of car owners evolved, which began to purchase the more fuel-efficient cars offered by the import market instead the stylish gas-guzzlers offered by domestic producers.44

Born in Moncton, New Brunswick in 1954, Rod grew up in a province which offered more alternatives to the automobile than did Saskatchewan. In a part of the country where trains and buses were a common part of life, Rod remembers the car as just another way to get around.45 Rather than an obsession with the automobile, Rod’s love for adventure would lead to his infatuation with a quite different mode of transportation: the motorcycle.

When he was 16, Rod’s need for speed inspired the purchase of his first motorcycle, a brand new 1970 Honda 350. In many ways, motorcycles brought to Rod the same feelings of masculinity and freedom that the automobile gave to the previous generations. “To me motorcycling is an adventure,” he states. “Every time I get on a motorcycle, even if it’s driving to work, it’s more exciting, more dangerous. It holds a lot more adventure.”46 Still, the motorcycle was also practical; a new motorcycle was cheaper and more fuel-efficient than a car.47

Rod’s choice of motorcycle reveals an interesting development in the automobile culture of the 1970s, the emergence of imported motor-vehicles. Honda, the largest motorcycle manufacturer at this time, was one of many foreign companies that was now selling cars (and motorcycles) in the North American market. 48 Despite North American economic measures aimed at protecting domestic firms and jobs, the reliability and fuel-efficiency of many imported cars was enough to appeal to buyers who wanted a functional, affordable automobile.49 In a similar way, Rod’s first car purchase was neither flashy nor conspicuous: a brand new, and reasonably priced 1975 Fiat, “a box on wheels,” as Rod fondly remembers it.50

The recent oil crisis of 1973 also played a role in his choice of car. “I remember thinking that big cars were on the way out,” he says. Fossil fuels were becoming more volatile, and Rod was worried that, an increasing dependence on oil imports would lead to the oil-producing nations “holding us ransom.”51 Rod was not alone in these feelings. Much of the public blamed the crisis on auto companies for producing cars that encouraged irresponsible consumption of gasoline. Others blamed consumers for encouraging the production of needlessly large cars.52

Adding to such sentiments was an increased consumer awareness of the effects of automobile related pollution on the environment. While many imported cars, such as the immensely popular Honda Civic, were well below the emission standards, domestic firms were failing to meet government mandated deadlines to make more environmentally-friendly vehicles.53 Suddenly it was no longer fashionable to drive a large American car; instead, as mentioned previous, Rod purchased a Fiat.

The crisis added to the rise in environmental sentiment aimed at large vehicles. The pollution caused by such cars was also a factor in many Canadians’ decision to switch to foreign- made cars. Just as such environmental concern had played a role in his choice of a motorcycle over a car, and it also played a role in his decision to buy his small, fuel-efficient Fiat.54

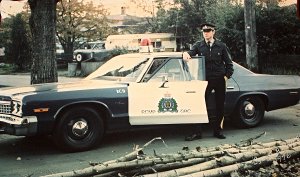

If Rod’s relationship with the automobile was ambivalent, his choice of career would change things. At the age of 19, in 1973, he enlisted with the RCMP, a career intimately aquatinted with the automobile. Working highway patrol in Greater Vancouver, Rod remembers such speed: “you’re always going fast . . . and being involved in high speed chases was definitely a rush.”55 Yet, even the excitement of highway patrol eventually became routine causing Rod to seek work in other departments. He worked in various places around British Columbia before eventually ending up in Cranbrook.56

Born in 1960 in Estevan, Carol Lapointe summed up her childhood experience with the car in one word “family.”57 Whether it was traveling to see relatives, or random trips camping, the Lapointes were always off on some adventure. The whole family - Charlie, Rose, the six kids and sometimes Grandma Shanner - would squish into their six passenger car; the back seat was so squished that Carol’s brother would often climb up into the back window and sleep. Even though there were not enough safety harnesses to go around, it mattered little, for the family “never wore seat-belts anyways” Carol remembers. 58

At first this phenomenon appears strange in a decade known for its crackdown on safety. In the Sixties, many of the dangerous design flaws of automobiles were brought to light. From he sharp, and often fatal, bumpers, ornaments, fenders, and tail-fins, to the unreliable handling of the Chevrolet Corvair (which easily flipped on a moment’s notice) it seemed that all aspects of car design were under attack.59 But if the demand for safety in car design was reaching new levels, much less was said about the necessity of safety harnesses. Although seat-belts were mandatory in all vehicles made after 1968, their use was optional, and many chose not to wear them. Moreover, it was not until the 1970s that any substantial legislation was passed that required drivers or passengers to “buckle up.”60

This new demand for safety did not, however, lessen the appeal of masculine cars. If the fifties had brought a broader acceptance of women as drivers, the Sixties brought a new categories of cars marketed on the idea of ruggedness and masculinity. Gone were the days of chrome and fins, real men were seen driving muscle cars. 61 When Carol was 16, she met Mike who drove such a car, a 1973 Dodge Challenger. “He was a hot guy, with a hot car,” she remembers. Mike, finding that Carol did not have a boyfriend, initiated a relationship and they later got married in 1979.62

For many teenagers of the Seventies, cars were much more than a way of getting around. “Not only were cars a life-line, they were also a love-line, “ Carol recalls. “In high school, guys with cars got dates.”63 Cars also enabled guys to take their girls on dates to the drive-in theatre, the beach, or to some private place, free from the watchful eyes of their parents. Carol remembers that some couples would go to Wascana Park, and “make out, make babies, or all of the above.”64 A car certainly came with romantic advantages.

In recent years, like many in their generation, Carol and her new husband Rod have distanced themselves from the automobile. Preferring to walk to work or bike, Rod and Carol, now see the automobile as a form of transport to use only when necessary. Rod’s pick-up truck is used primarily for errands in Cranbrook - where public transit is all but non-existent - and as a means to reach the camping, hiking, and fishing spots that the couple love to visit. Moreover, in comparison to a generation ago, where it was desirable to work towards a second car, Rod and Carol are downsizing, recently selling their second vehicle. “You don’t need two vehicles to maintain a healthy lifestyle,” Carol says.65

The environmentally unfriendly aspect of owning cars has also become paramount in Rod and Carol’s lives. Aware of the emissions and the physical damage big vehicles cause on the landscape, the couple plans to further downsize, from their truck to a smaller vehicle. Such concerns have also led the couple to return to the motorcycle as a source of transportation. Consequently, the thrill that motorcycles held for Rod in the past has been reborn. He still looks to his bike with passion and excitement, only now he has Carol to share these great adventures with him.66

Beginning with the feelings of liberation that the automobile brought to my Grandparents, and continuing on to the ambivalent relationship that my parents have with the car in modern times, my family has seen and experienced many of the major changes that motorization brought for Canadians. From Buicks to Hondas, motor-vehicles have served as agents of mobility, romance, employment, and adventure, creating memories and anecdotes that have been planted in the memory of my family’s past. As I look into a future filled with automobile related problems, such as a finite oil supply, climate change, and the economic uncertainty of the major American car companies, I wonder what role the automobile will play in my family’s future. Will the next generation of drivers be capable of reconciling the automobile with the environment? Or will the automobile be replaced by a more efficient form of transportation? If the future of my family’s relationship with the car remains a story yet untold, its past has been vividly, and colourfully recounted in this paper. May both the memories, and those who shared them, enjoy a long-life and an enriched future.

Primary Sources

Katchur, Julia. Interview by the author, 23 February, 2009.

Lapointe, Carol, Interview by the author, personal interview, 17 February, 2009.

Lapointe, Charlie, Interview by the author, 15 February, 2009.

Lapointe, Rose, Interview by the author, 15 February, 2009.

Wood, Rod, Interview by the author, 18 February, 2009.

Published Sources

Anastakis, Dimitry. Car Nation: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Transformation Behind the Wheel. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., 2008.

Brandon, Ruth. Auto Mobile: How the Car Changed Life. London: Pan Macmillan Ltd., 2002.

Douglas, Tommy. “The Highlights of the Dirty Thirties.” In The Dirty Thirties in Prairie Canada ed. by D. Francis and H. Ganzevoort. Vancouver: G. A. Roedde Ltd., 1980, 163-173.

Holtz Kay, Jane. Asphalt Nation: How the Automobile Took Over America and How We Can Take It Back. New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1997.

Setright, L. J. K. Drive On! A Social History of the Motor Car. Beccles, UK: Palawan Press Ltd., 2002.

Volti, Rudi. Cars and Culture: The Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Wollen, Peter. “Introduction: Cars and Culture.” In Autotopia: Cars and Culture. ed. by Peter Wollen and Joe Karr. Hong Kong: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2002, 10-20.

Images

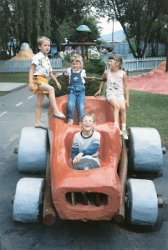

Cover Image - Mike Katchur - Steve behind the wheel with Michelle and Julie Katchur, as well as friend, Joshua Baxter, 1990, Kelowna, BC, collection of Steve Katchur.

Figure 1 - Omer Lapointe and Family in the 1926 Model T, c1928, Glamis, SK, collection of Jim Best.

Figure 2 - Anna Shanner, Charlie with Ralph’s Shanner’s 1952 Oldsmobile, c1954, Estevan, collection of Carol Lapointe.

Figure 3 - Ralph Shanner and Family with the 1935 Dodge Truck, c1943, The family farm outside of Estevan, collection of Rose Lapointe.

Figure 4 - Anna Shanner, Ralph Shanner and Mr. Wingert, next to the Bombardier, c1952 The family farm outside of Estevan, collection of Rose Lapointe.

Figure 5 - Peter, Julia, and Elsie next to the Family Panel Truck, c1946, Wilsonville, Ontario, collection of Julia Katchur.

Figure 6 - Charlie Lapointe, Rose Shanner, Winn Lapointe, Anna Shanner, Lloyd Shanner, Ralph Shanner and the 1955 Buick, 1955, Macdowell, SK, collection of Rose Lapointe.

Figure 7 - Lois Wood, Rod Wood with 1970 Honda, 1971, Munton, NB, collection of Rod Wood.

Figure 8 - Pat Sullivan, Rod Wood with Police Cruiser, c1975, Burnaby, collection of Rod Wood.

Figure 9 - Mike Katchur with his 1970 Dodge Challenger, c1976, Regina, collection of Carol Lapointe.

Figure 10 - Steve Katchur, Rod Wood and Carol Lapointe with Yamaha V-Star 1300, 2008, Canmore, AB, collection of Steve Katchur.

Endnotes

1 Rose Lapointe, personal interview, 15 February, 2009. L. J. K. Setright,

2 Drive On! A Social History of the Motor Car. (Beccles, UK: Palawan Press Ltd., 2002), 186.

3 Dimitry Anastakis, Car Nation: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Transformation Behind the Wheel. (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., 2008), 32-33.

4 Julia Katchur, personal interview, 23 February, 2008.

5 Ruth Brandon, Auto Mobile: How the Car Changed Life. (London: Pan Macmillan Ltd., 2002), 239.

6 Julia Katchur.

7 Anastakis, 34.

8 Julia Katchur.

9 Brandon, 122.

10 Julia Katchur.

11 Charlie Lapointe, personal interview, 15 February, 2009.

12 Brandon, 90-91.

13 Tommy Douglas, “The Highlights of the Dirty Thirties.” In The Dirty Thirties in Prairie Canada ed. by D. Francis and H. Ganzevoort. (Vancouver: G. A. Roedde Ltd., 1980), 163.

14 Douglas, 163.

15 Charlie Lapointe.

16 Douglas, 163-4.

17 Brandon, 250-52.

18 Charlie Lapointe.

19 Charlie Lapointe.

20 Douglas, 164-5.

21 Charlie Laponte.

22 Charlie Laponte.

23 Peter Wollen, “Introduction: Cars and Culture.” In Autotopia: Cars and Culture. ed. by Peter Wollen and Joe Karr. (Hong Kong: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2002), 13.

24 Charlie Lapointe.

25 Rose Lapointe.

26 Rose Lapointe.

27 Anastakis, 32.

28 Volti, 62.

29 Rose Lapointe.

30 Anastakis, 55-60.

31 Julia Katchur.

32 Setright, 260-62.

33 Julia Katchur.

34 Anastakis, 58-59.

35 Rose Lapointe.

36 Anastakis, 29.

37 Rudy Volti, Cars and Culture: The Life Story of a Technology. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004), 52.

38 Charlie Lapointe.

39 Charlie Lapointe.

40 Anastakis, 66-68.

41 Charlie Lapointe.

42 Charlie Lapointe.

43 Charlie Lapointe.

44 Volti, 115.

45 Rod Wood.

46 Rod Wood.

47 Volti, 124.

48 Volti, 130

49 Ananaskis, 77.

50 Rod Wood.

51 Rod Wood.

52 Ananaskis, 77.

53 Anastakis, 83.

54 Rod Wood.

55 Rod Wood.

56 Rod Wood.

57 Carol Lapointe, personal interview, 17 February, 2009.

58 Carol Lapointe.

59 Brandon, 309-312.

60 Setright, 113-14, 183.

61 Anastakis, 60.

62 Carol Lapointe.

63 Carol Lapointe.

64 Carol Lapointe.

65 Carol Lapointe.

66 Rod Wood.