The Family Automobile

An ‘Auto-Biography’

by: Kelsi Warawa

March 19, 2009

The definition of an automobile is a self-propelled vehicle used for passenger transportation, for many families though, the automobile is more than simply a means of getting around.1 The automobile has evolved immensely over the centuries, since the steam-powered vehicles of Nicholas Cugnot first appeared in the late 1760s, revolutionizing the lives of people through out the world.2 With this advancement of the automobile, it is evident that the way of life for families has also changed in order to adapt to the environment that the automobile has created.

My family has always had a passion for the automobile, which is evident in how the automobile shaped our family life. This paper will provide historical evidence of how the automobile has influenced and transformed family life over the decades, through the experiences of the Warawa family. Beginning in the late 1920s with the difficulties faced by early drivers of the automobile, the paper will then proceed on to how the automobile personifies the owner. The paper will include family memories from both the Cope side and the Warawa side. My great aunt, Joyce Booker; my aunt, Sheila Donaldson; and my mother, Brenda Warawa will provide information about the history of the automobile on the Cope side going back to my great grandparents. The experiences of the Warawa family include recollections from my grandparents Ed and Lois Warawa; and my father Robert Warawa that will also go back to my great grandfather, Joe Sunderman.

Over the years, families have changed and needs have changed but the respect for the automobile has remained evident. The early years of the automobile shaped the future by paving the way for an independence that has been valued through the generations. In the Warawa family history, the automobile has been representative of the lifestyle at the given time. As the design and technology of the automobile changes, so do the needs of the family. Though circumstance may dictate the requirements of the automobile, there has always been a deep respect for its importance in the family lifestyle.

Joyce Booker remembers the family getting their first automobile and how it brought prestige and independence into their life. “At that time it was a luxury item, the major mode of transportation was still horse and buggy or sleigh.”3 Living in an outlying farming community in Saskatchewan the automobile provided a link to the city. The automobile impacted rural life significantly as it provided means of escape from the isolation due to “lack of contact, with other people, economic handicaps because of limited access to markets and inferior public services.”4 This being said the independence and freedom that the automobile provided did not come easily in the beginning. A lack of infrastructure made travel difficult in the beginning. The most significant barrier felt by families was poor road conditions. For the most part driving in the winter was impossible as there were no modern technologies to clear roads. The snowdrifts that piled up along the fence lines made it difficult, even when there was little snow. Booker remembers times when the family would cut through neighbours farm fields by taking down fences along the way, in order to reach the closet highway, which was just over two miles away.5

The Warawa side of the family also experienced isolation as they lived on a homestead in Northern Alberta. This is what led Joe Sunderman to purchase a school bus in the mid 1940s. The first of its kind in the area it was a modified GMC truck with a set of bench seats on each side of the box. It provided means of transportation for eight students in the countryside, who previously had no other options, but to study by correspondence. By providing this link for students to the city, more were able to attend public school for their education. Schooling in the city was of much higher quality, as there were more resources available to aid in the education.6 Before the presence of the automobile, schooling in the city was not a possibility. Sunderman started a trend in the area and soon more and more families were investing in a bus in order to provide adequate means of education for the children in their area. Evidently, the automobile brought independence and created opportunities that would not have been possible otherwise for families living in isolated communities.

The lack of infrastructure made traveling a challenge in Northern Alberta as well. Lois Warawa chuckled to herself as she thought about picnics the family would take in the Model A and the panic that would set in at any sight of a storm cloud approaching. “Everyone would scramble to pack everything up and get out of there as quickly as possible, no one wanted to be on the roads when the rain hit.”7 Most automobiles were unable to maneuver through wet, muddy clay roads without becoming stuck. The numerous potholes on the roads did not help matters, which meant the use of the automobile was limited, until roads became more adequate.

Driving the automobile was another obstacle faced in the early years due to a number of reasons. Joe Sunderman’s first vehicle bought in the 1930s was “a well-used Model A that was built like a box.”8 It was not at all uncommon that only the men knew how to drive the vehicles. Women drivers threatened the long-standing social expectations and practices of women in society.9 After the First World War, the amount of women drivers spiked due to the lack of men available to drive.10 This trend did not affect the rural areas as quickly since the automobiles were usually older and more difficult to handle, due to their style of mechanization. Sunderman was fortunate to be able to afford this luxury item for his family, in good road conditions it meant faster travel times to town to pick up groceries or the mail.11 Every trip in the Model A was an adventure states Lois Warawa as she recaps the trips to the grocery store.

It was quite an ordeal, to begin with if the car did not get enough speed coming up to the hill to get out of our driveway it would roll all the way back down the hill. Then there was the problem of the gate at the top of the hill. My sister Doreen and I would be riding in the backseat and Dad would drive like crazy in hopes of making it up the hill. We’d get near the top and Doreen and I would hop out of the car with Dad still chugging along, run ahead, pull open the gate, let Dad roll through, shut it behind him and then run and catch back up with the car, hop in and be on our way. We had to be fast though as we did not want to risk the car stopping. The hand crank to start it was tricky and would delay our trip if Dad couldn’t get it started again.12

With the onset of the automobile, there was a “transformation in recreational habits” of the family.13 It marked the beginning of short pleasure trips and longer vacations away from the home.14 This phenomenon eventually led to change in the architectural design of the house. Rooms such as the parlor were no longer a necessity as people enjoyed their leisure time away from the home.15 Carports and garages became necessary to store the automobile as well. The highways allowed an economic form of travel that was possible by ones own private means.16 Camping has always been a big part of both the Cope and Warawa lifestyle and this is still true today. While over the decades, the way of camping has evolved greatly, going from simple tents to trailers with full amenities; the idea of recreational travel for leisure has remained the same.

The automobile revolutionized camping. In the early years camping was a way to reconnect with nature. The emergence of the automobile increased visits to national parks tenfold.17 Campers would convert automobiles into make shift shelter and were able to camp anywhere as there were no set guidelines. Camping was not for the fearful as a lack of infrastructure was all part of the adventure in the early days. One such adventure for the Cope family was on a trip to the Peace River in 1929. The only route available to cross the river was a train bridge. “Everyone had to get out of the car and walk while Russell Cope drove the car over the bridge rail by rail. We all just held our breath hoping a train wasn’t coming.”18

Sheila Donaldson and Brenda Warawa also have numerous memories of camping in their childhood. Before the Cope family had a trailer, they would all sleep in the automobile.

Camping out in Saskatchewan one time we were all sleeping in the Rambler, the seats folded down into a bed. It was too cramped for Dad so he slept under the Rambler. The next morning when we woke up we saw the sign ‘Please Do Not Feed the Bears.’ Dad was lucky there were no visitors that night!19

After that experience, the Cope family purchased a Teardrop trailer. For their family of five this trailer was still too small. Helen Cope ended up sleeping in the vehicle, as she felt too claustrophobic in the trailer.20 Clifford Cope enjoyed building, so decided to build their own tent trailer that would accommodate the whole family.21 Sheila Donaldson remembers this tent trailer well. “One particular trip was quite exciting. We were driving down the highway and the top flew off, it had not been strapped down properly. It was quite a scene, our bedding was all over the highway!”22

Camping with the automobile clearly was more then just a way of interacting with nature. It allowed for leisure time spent with the entire family. This helped to shape the family while greatly influencing the family’s needs and desires in an automobile. These stories are evident of the crucial role the automobile played in allowing families to enjoy this lifestyle.

Undoubtedly, the automobile played a significant role in shaping the family lifestyle. The automobile personifies the owner and represents their lifestyle and their stage of life. Automobiles are chosen based on desire, need and convenience. While finances and circumstances influence these choices, the automobile is still representative of the owner.

Ed Warawa has gone through a number of different automobiles. Ed’s first car was a ‘41 Buick purchased in 1953. “The big ol’ light blue clunker” was one of the many used vehicles owned.23 In 1958, Ed purchased a ‘56 Chevy Bel-Air Coupe, “it wasn’t new but it only had 10,000 miles on it.”24 Today this automobile is a collector car. It was this automobile that Lois learned to drive on, as it was an automatic. Work and family needs meant that it had become a necessity for Lois to be able to drive as well. Having two drivers in the family by this time was the norm, especially as more and more families found it necessary to own two vehicles. The needs of the family were what sprung on this change. The Bel-Air was loved by the family but they were forced to sell it before they moved to Germany for a military posting. In Soest, Germany, Ed purchased an Opel Record, which was the German equivalent of a GM Chevy II.25 With this Opel, the Warawa family camped and traveled all over Europe.

Photograph 4- Lois Warawa, Ed Warawa’s ’56 Chevy Bel Air Coupe, 1958, family collection of Lois Warawa.

The Warawa’s travels were not without incident. While traveling in Europe, there was a problem with a noise in the rear. Ed wanted to discover where the noise was coming from so told Robert to climb into the trunk. Lois refused to have one of the kids go back there. Instead, Lois herself climbed in; high heels, skirt and beehive hairdo and all, to distinguish where the noise was coming from!

It certainly was quite the site along the autobahn. Everyone’s eyes were popping as they slowed down to see Lois crawl out of the trunk. The autobahns have more traffic and travel at higher speeds compared to our highways. The fact they slowed down was quite something. Turns out the problem had been a rear bearing so it was fixed and we were on our way.26

Without a doubt, finances and family lifestyle have shaped Brenda Warawa’s automobile ownership. After graduation from nursing, Brenda purchased a brand new Honda Accord Hatchback. An automobile had become necessary in order to commute to and from work. Upon being married, the Honda was traded in for a Blazer, as 4-wheel drive was necessary to get up the mountain Robert and Brenda now lived on. This blazer started the trend of Brenda owning the family vehicle and Robert keeping his trucks and collectibles.

Similar to most families, Robert and Brenda hit a point where the minivan was deemed necessary. The minivan provided means to haul around the family, the groceries and to pull the tent trailer, all while providing convenience. Of course, the minivan was Brenda’s vehicle, as “Robert didn’t want to be caught dead driving the minivan.”27 Subsequent to trying out a 1990 used Chrysler Minivan, Robert and Brenda upgraded to a brand new ‘95 Chrysler Minivan. After owning it for less than six months, it was totaled after popping out of gear, when at the top of the driveway, and rolling down into the ditch. Brenda suffered from a broken neck and needless to say never wanted to drive a minivan again.28 Inspectors from Detroit, Michigan were sent out to inspect the minivan. The problem was with the gearshift as it was made with a weak pin and had a tendency to slip out of park.29 Within a few years, Chrysler changed their mechanism of the gearshift so it was heavier duty and had a more precise locking mechanism.

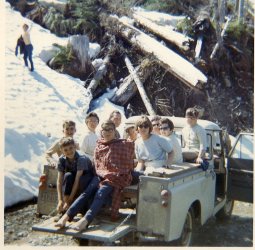

Photograph 5- Brenda Warawa, Warawa Annual Vacation to Oliver, 1992, family collection of Brenda Warawa.

Due to changes in family lifestyle, Robert and Brenda decided to return to a four-wheel drive automobile, picking a ‘95 Jeep Cherokee.30 This would allow them to start hauling a trailer again, which was a step up from the smaller tent trailer. The problem with the Jeep was that it was a narrower vehicle, which made it difficult to pull the heavy trailer. This led to a frightening experience on the family’s annual camping trip to Tuc el Nuit Lake in Oliver. Brenda recalls the drive through Manning Park:

The trailer started to sway dangerously, pulling the car with it. Dad was just trying to keep it on the road and you were in the backseat yelling WHEEeee, thinking it was a roller coaster ride. I had my foot on the breaks the rest of the way to Oliver and I was only the passenger! Upon the return from that trip we got rid of that vehicle pretty fast.31

Once again, Brenda’s vehicle choice was influenced by the family needs, as Robert’s truck was not large enough for the whole family. Brenda chose a ‘96 GMC Yukon. It had the towing capacity needed, 4-wheel drive, comfort and was large enough for the entire family, even including the dogs. After owning the Yukon for a number of years, problems occurred, and with the warranty almost up, it was time for change. Gas prices were starting to take a noticeable jump. Robert and Brenda decided to sell the trailer and resort to a motor home. This way a large vehicle was not necessary for everyday travel. Similar to others, Brenda had become attached to the security felt by driving a larger vehicle and the convenience of being able to drive in all weather conditions. An SUV still fit the family lifestyle so she ended up choosing a ‘03 Honda CRV. The Honda fit all these needs in a smaller package, which suited gas prices and continues to fit the family lifestyle today. In Brenda’s future, what does she see? “My dream car would be a Mercedes sports car but the reliable Honda SUV is probably more in the cards!“32

Robert Warawa has always had a passion for the automobile. At the age of sixteen, he got his motorcycle license and a ‘63 Honda Dream 150cc Motorcycle. Shortly after he purchased a used ‘70 Toyota Corolla Coupe, “it was the only thing I could afford at the time as a student and it was cheap on gas.”33 Robert went through a number of automobiles in the early years including a ‘70 Nova SS Sport Coupe, ‘74 Corvette and a ‘76 Corvette which he traded in right before meeting Brenda Warawa for his only brand new vehicle ever purchased, a ‘80 GMC Brown Sierra Stepside. With this truck his love for GM started to take hold.

Brenda recalls how important this truck was to Robert with a story during their dating years.

When we were dating he had a flat tire coming to Burnaby and missed our date. He didn’t have the wheel lock to undo his mag wheels so had to chip the lug nuts off the tire one by one. Needless to say he missed the date.” Robert cuts in with “but at least I phoned” with the reply from Brenda being “yeah the next day! Actually you seemed to have a problem with dates, my first Harley ride it broke down!” Again, Robert interrupts, “that never happened.” “Yes it did, you had to actually kick it to get it started again and we were way out in the middle of no where.34

Unfortunately, Robert was forced to trade the ‘80 GMC when he married Brenda as they were building a new house and needed the money. He ended up with his Father Ed’s old rusted out ’74 Toyota truck. “It was so rusty you could see the road through the floorboards.”35 This truck was definitely not up to Robert’s meticulous automobile standards. He kept it going for a few years though as the financial situation meant he was unable to have the vehicle of choice.

Photograph 7- Brenda Warawa, Rusty Toyota, Honda Accord & brand new home, 1982, family collection of Brenda Warawa

Eventually Robert was able to get another GMC Sierra, a ‘80 known as Old Betsy because he had her for sixteen years.36 Old Betsy was a simple, reliable and well cared for truck that Robert was attached to. A few years after selling Old Betsy, on the annual trip to Oliver, Robert spotted her and had to go hunt down the owner to see how she was running. Turns out the man loved the truck and could not believe how well cared for it had been.

Photograph 8- Bob Warawa, Travels with Old Betsy, 1986, family collection of Brenda Warawa.

In the early 1980s, Robert started to build and restore automobiles himself.

Brenda no longer wanted me riding my motorcycles, which I preferred over the cars, because of the dangers involved. My disposable income was growing at that time and I developed a love for mechanics and vintage vehicles of yesterday. You take a lot of pride in something you’ve done yourself, it’s an art form.37

As a collectible car enthusiast Robert Warawa spends multiples of “time, money, emotion and effort on acquiring, learning, and caring” about automobiles.38 With his own workshop specifically for his automobile equipment, tools and parts, there is no question that the passion for automobiles is more than a simple hobby.

Technology was changing rapidly and Robert wanted to be able to do work on the automobiles himself, rather than having to take them into mechanics. Robert’s first automobile restoration project was a ‘65 Corvette, prior to that he had been restoring motorcycles. The key to automobile restoration is to “return the vehicle to its condition at the time of original sale” although that does not mean avoiding the use of new technologies such as safety glass or motors that are more efficient.39

After a complete restoration of a ‘31 Ford Roadster, ‘Old Annabelle’, which the previous owner had let go, Robert decided to do a U-Build Project. Robert chose the ‘32 Ford Roadster, “in hot rod culture the ‘32 is the cream of the hot rods, due to the Bonneville Salt Flat races in the 1930s.”40 The ‘32 Ford was a significant automobile for the Ford Company. Due to competition from GM and Chrysler, Ford products were in decline.41 This spurred on Fords radical move to create a V-8 engine. Ford himself supervised the project, in hopes of outdoing Chryslers six-cylinder engine that had been designed in the late 1920s.42 The first Fords with V-8 engines were simplistic but the advertisers ensured the buyer that the new Ford V-8 experience was “the greatest thrill in motoring.”43 The development of the ‘32 was “truly an advanced automobile in all respects, selling at an exceptionally low price.44” Even though it was considered one of Fords greatest creations, it still failed to revitalize the company at that time. Today it is a collector car with a good resale value, which has what led Robert to build three ‘32 Ford Roadsters. For the first time ever though the completed ‘32 sitting in the garage is getting no calls, “it’s the longest vehicle that I’ve had without a buyer.”45

Over the years Robert has had owned numerous motorcycles, hotrods and muscle cars predominantly American. He has probably owned forty plus different project cars and never lost money on any resales. In his words, “if you buy the right collector vehicle for the right price there is always a market for it.”46 The shortest automobile owned sat in the garage for less than a day before he had turned around and sold it. True to how the automobile personifies its owner there have been some interesting characters purchasing vehicles from Robert. Money has been paid in all different ways, but it has always turned out to be legitimate.

Different vehicles attract different characters, one buyer paid cash in a brown paper bag filled with $20 bills. Brenda whipped down to the bank to make sure it was not counterfeit. Everything was legit though. Motorcycles usually attract the rougher crowd where the collectible cars usually have an age range of 40-60. They are the ones who have the money to purchase them and usually also have an interest from childhood.47

Evidently, with the ’32 Ford Roaster failing to have any potential buyers, the future of collectible cars is undecided. With today’s cars being technologically advanced, unlike the simple cars of the past, it will become harder for automobile enthusiasts to restore automobiles themselves. Today, automobiles are throw away. Computer parts and electrical parts will not be obtainable to restore these cars leaving no future for them. Automobile technology clearly has evolved, with automobiles being more reliable, safer and environmentally friendly. All this, while providing a vast degree of choice in design, colour and comfort for the owner. The problem is that the owners of these modern vehicles only see them as a mode of practical transportation because they all are homogenized, lacking style, performance and personality. Mass production has resulted in automobiles simply becoming boxes on wheels rather than works of art that will be valued and collected through the years.

Families change. Needs change. Automobiles change. This is evident as you look back on the history of automobiles in the Warawa family. Similar to past generations, the way of life for families will continually adapt to the future changes the automobile presents.

Bibliography:

Belk, Russell W., “Men and Their Machines.” Advances in Consumer Research, 31:1 2004.

Berger, Michael L., “Women Drivers!: The Emergence of Folklore and Stereotypic Opinions Concerning Feminine Automotive Behavior,” Women Studies in Forum, 9:3, 1986.

Booker, Joyce. Interview by the author, 07 March 2009.

Borhek, J. T., Rods, Choppers, and Restorations: The Modification and Re-creation of Production Motor Vehicles in America, Journal of Popular Culture, 22:4, 1989:Spring.

Donaldson, Sheila. Interview by the author, 07 March 2009.

Flink, James J. The Automobile Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1988

Holtz Kay, Jane., Asphalt Nation: How the Automobile Took Over America and How We Can Take It Back, Berkeley and Los Angeles California: University of California Press, 1997.

Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 1989.

Rae, John B. The Road and the Car in American Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1971.

Setright, L.J.K. Drive On! The Social History of the Motor Car. London, Granta Books, 2003.

Volti, Rudi, Cars and Culture: The Life Story of a Technology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Warawa, Robert. Interview by the author, 22 February 2009.

Warawa, Brenda. Interview by the author, 22 February 2009.

Warawa, Ed. Interview by the author, 07 March 2009.

Warawa, Lois. Interview by the author, 07 March 2009.

Endnotes

1“Automobile,” Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 1989.

2 Rudi Volti, Cars and Culture: The Life Story of a Technology (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2006), 2.

3 Joyce Booker, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

4 Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, 155.

5 Joyce Booker, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

6 John B. Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life (Clinton, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1971), 164.

7 Lois Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

8 Lois Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

9 Michael L. Berger, “Women Drivers!: The Emergence of Folklore and Stereotypic Opinions Concerning Feminine Automotive Behavior,” Women Studies in Forum (Vol. 9 No. 3 1986): 258.

10 Berger, “Women Drivers!,” 258.

11 Lois Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

12 Lois Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

13 Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, 138.

14 Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, 138.

15 Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, 138.

16 Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, 139.

17 Jane Holtz Kay, Asphalt Nation: How the Automobile Took Over America and How We Can Take It Back, (Berkeley and Los Angeles California: University of California Press, 1997) 172.

18 Joyce Booker, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

19 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

20 Sheila Donaldson, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

21 Sheila Donaldson, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

22 Sheila Donaldson, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

23 Ed Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

24 Ed Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

25 Ed Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

26 Ed Warawa, personal interview, 07 March 2009.

27 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

28 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

29 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

30 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

31 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

32 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

33 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

34 Robert and Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

35 Brenda Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

36 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

37 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

38 Belk, Russell W., “Men and Their Machines.” Advances in Consumer Research, 31:1, (2004), 273.

39 J. T. Borhek, Rods, Choppers, and Restorations: The Modification and Re-creation of Production Motor Vehicles in America, Journal of Popular Culture, 22:4 (1989:Spring).

40 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

41 James J. Flink, The Automobile Age (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1988), 231.

42 Flink, The Automobile Age, 231.

43 L.J.K. Setright, Drive On! A Social History of the Motor Car ( London: Granta Books, 2003), 66.

44 Flink, The Automobile Age, 230.

45 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

46 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.

47 Robert Warawa, personal interview, 22 February 2009.