Land

Taxation

As Kain and Baigent state the

collecting of taxes and state revenues from land and resources drawn

from that

land, has been the overwhelming reason for the cadastral mapping of

land in

Europe (Kain and Baigent 336). In this sense the modern

European

states deployed cadastral systems for the

same reasons as the Roman Empire did, to organize the collection of

state

revenue (Kain and Baigent 336). In the Seventeenth century

Sweden

and the Netherlands used cadastral maps for

this specific purpose (Kain and Baigent 336). After the

Thirty

Years War, economic hardship pushed more governments to employ

cadastral surveys as methods to increase the efficiency of drawing

revenue from

their territory (Kain and Baigent 338).

Back to Top

Land Reclamation

In the sixteenth and

seventeenth

centuries in the Netherlands cadastral maps were used to layout land

allotments

formed after the draining of coastal marshes and to

“display” these lots as a

way to attract shareholders and investors who wished to purchase land

(Kain and Baigent 332). Towards similar ends maps were

utilized

in the draining of the Eastern English

Fenland, coastal areas of northern Germany, and in the Veneto valleys

under the

control of the Venetian government (Kain and Baigent 332).

Back to Top

Evaluation

and

Management of State Land Resources

Cadastral maps, because they aim at

creating an exhaustive and accurate account of an areas land holdings,

have

been used as way of creating an inventory of a state’s

resources. One such

example of this is the use of cadastral mapping in Europe to better

assess and

manage timber exploitation. From the seventeenth century on the use of

cadastral mapping techniques for this purpose had been employed in

England,

France, Russia, Germany, and Norway (Kain and Baigent 333).

Back to Top

Land

Redistribution

and Enclosure

The enclosure movement in England

was a prime example of how professional surveyors and cadastral mapping

were

used in the service of the state. As Kain and Baigent argue the goal

for

greater agricultural production, based upon

“rational” and “uniform”

methods of

organization were the underlying reasons for the abolishment of common

property

in England (Kain and Baigent 334).

Laura Brace has

argued that the

promoters of this enclosure movement (the

“improvers” or advocates of

“husbandry”) based this reorganization upon divine

right. God had

created the

earth for the manipulation of “man” and,

“those involved in husbandry

and

improvement felt themselves engaged in a tremendous project to convert

the

desolate wastes into fruitful fields, and the wilderness into

comfortable

habitations” (Brace 6). In their

view the English commons were nothing more than places of waste and

chaos,

generating “unemployment, idleness, vagrancy, and

crime” (Brace 9).

Brace goes on to argue that the process of enclosure would

help to

replace this

chaos with, “a neat patchwork of hedged fields securely held

as private

property

by virtuous improving individuals” (Brace 9). As

Kain and Baigent note

it was the surveyor and his goal of a cadastral

mapping that would be fundamental in creating this

“patchwork” of

property

relations (Kain and Baigent 334).

|

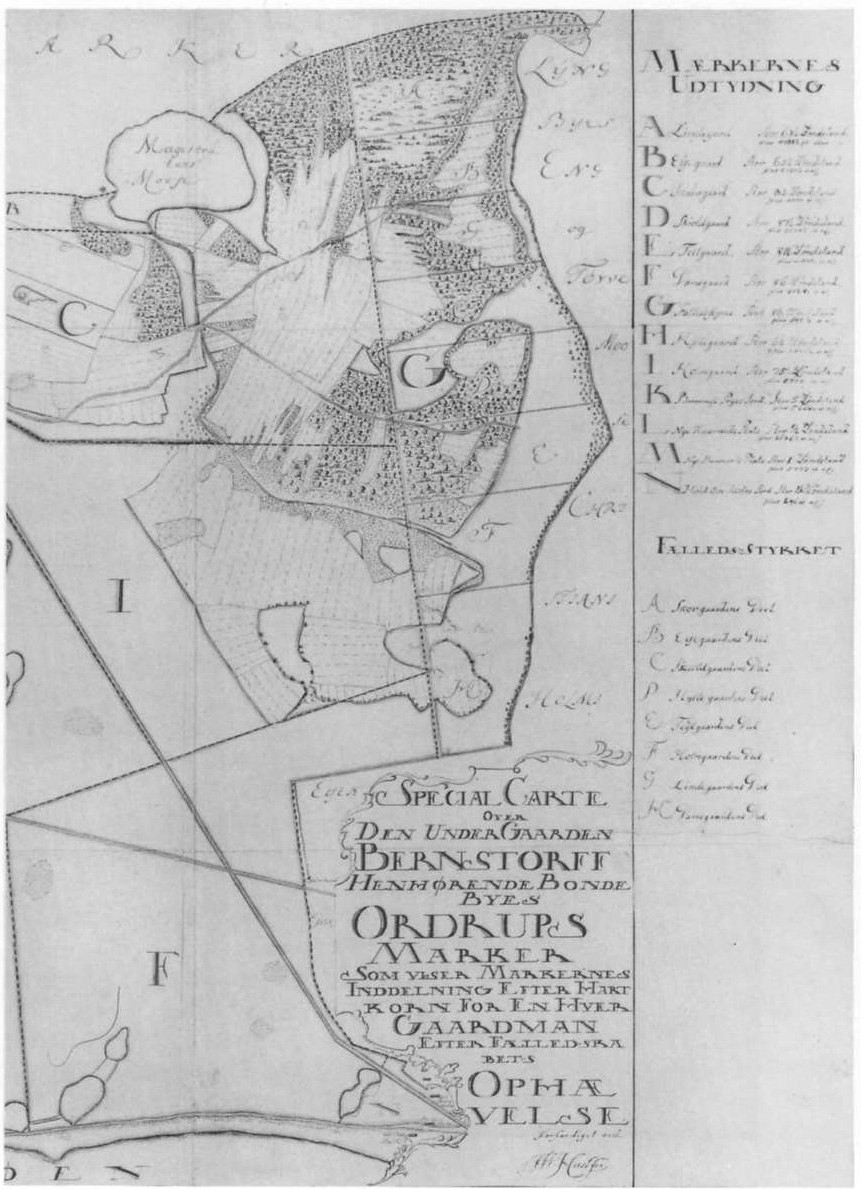

Map of Enclosed Land

|

Back to Top

Symbols

of State

Control over Land

A cadastral map, combined with a

coat of arms, or an imperial insignia could be seen as a powerful

symbol for

the displaying of a state’s or individuals sovereignty over

its

territory (Kain and Baigent 340). The European Empires

coloured

their colonial possessions on world maps as just

such an example of displaying their authority, power and status.

Benedict

Anderson has referred to this phenomenon as

“map-as-logo”

whereby a known map,

(say of an Empire's colonies) could be created and recreated,

“available for

transfer to posters, official seals, letter heads, magazine and

textbook

covers, tablecloths and hotel walls” (Anderson 175).

For

Anderson this processes both aids in the expansion of colonial

nationalism

and anti-colonial nationalism as symbol to rally both around, and

against (Anderson 175).

Thus cadastral maps had political and cultural implication beyond

simply the

administration of property for fiscal reasons.

Back to Top

Colonial Settlement

The reasons for the mass exodus

from Europe to the New World are diverse but the desire for land was

among one

of the preeminent factors that drew the Europeans. As a result the land

that

they took, be it in Ireland or North America, had to be organized into

a system

that was conducive to state administration. Cadastral mapping then was

a key

mechanism for the expansion of colonialism.

In

1858 English surveyors were sent

to Muster Ireland to plan out a new village. It was to be four miles

square and

sub-divided into various sized lots with goal of crating a

“balanced rural

society” (Kain and Baigent 335). In the end

the surveyors were unable to maintain their demarcations which were

resisted by

local residents and the plan at Muster failed for the moment. However,

the use

of cadastral mapping was used again after the 1641 rebellion when

nearly half

of the country was confiscated by the English (Kain and Baigent 335).

Between 1665-1669 the Down Survey created a cadastral map

which

listed all

confiscated lands, reorganizing them into new

“rational”

holdings, and produced

an inventory of the potential use of land into four categories:

cultivable,

bog, mountain, and wood (Kain and Baigent 336). Surveying

then

created both the conditions for the reorganization of domestic

Irish property and land systems into ones that suited the goals and

values of

the colonial administration. In the confiscated areas land was mapped,

its

human population and the potential resources drawn from that land were

more

“legible” for state officials.

Back to Top