Success and Permanence

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century architecture held increasing interest among pioneering British Columbians. As settlements grew writers rarely missed an opportunity to comment on the number of churches a community had to its credit. The presence of church buildings was seen as integral to both the permanence and success of a community.1Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 71. In essence, the establishment of church buildings signaled not only a comitment by the scared community, but also the inevitable advancement and permanence of the whole population.

The evaluation of church buildings in the press was reflective of the complex pioneer universe as it was understood in nineteenth century British Columbia. This intricate world vision maintained secular and scared as two distinct worlds, yet at the same time they were inextricably intertwined. The construction and condition of church buildings were perceived to reflect the virtues of the community. How a community cared for its place of worship was seen as a reflection of the community as a whole. Attention to church architecture was seen to proclaim not only the moral value of the community but its work ethic as well.2Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 71-72.

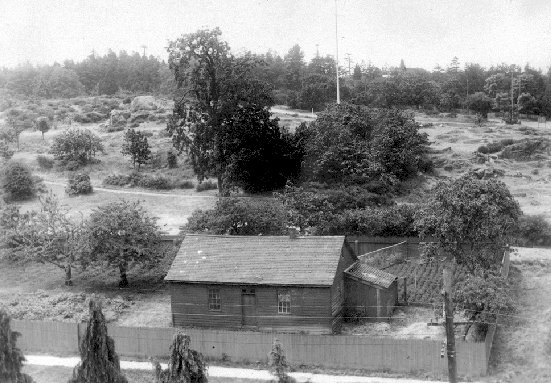

We can see from these two pictures of St. Ann`s, the first one in 1856 and the second in 1871, this sense of permanence and success can easily be represented in buildings. The 1856 building is little more than a shack. Nevertheless, we should not be quick to judge the modesty of the 1856 building. Often no matter how humble a church building was it still stood as tangible evidence to the comitment and intent to permanence of religious leaders.3Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 74.

If the 1856 building stood as evidence to intent then the 1871 building stood as unqualified proof of permanence. The monolithic structure at a then soaring four floors

The 1871 building dominates the Victoria skyline was reported “with boosterism” in the British Colonist as a “six storey building.”4Edward Mills and Sally Coutts, A History of the Academy and the Sisters of St. Ann in British Columbia, Canadian Inventory of Historic Building, Parks Canada, no date, pg. 13.

A.J. Langley’s book, A Glance at British Columbia and Vancouver’s Island, made a direct link between the commercial buildings and the prospect of success for the new colony they held with the appearance of a couple of church spires on Victoria’s skyline. Martin Segger argued that this assessment of Victoria’s skyline is a comparative analysis of how closely Victoria resembles England, or how picturesque the skyline was.5Martin Segger and Douglas Franklin, Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture (Victoria: Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), pg. 11-12. Segger seems to suggest that if the skyline is indeed agreeable then, at least for Langley, the city as likley to succeed.

An important component of any denomination trying to establish itself in a pioneer community is to shake off the appearance of transience.6Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 72. Creating a reassuring sense of permanence was not easy, but one of the most effective ways to persuade pioneers was to build buildings that gave an impression of permanence.

Footnotes

1Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 71.

2Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 71-72.

3Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 73.

4Edward Mills and Sally Coutts, A History of the Academy and the Sisters of St. Ann in British Columbia, Canadian Inventory of Historic Building, Parks Canada, no date, pg. 13.

5Martin Segger and Douglas Franklin, Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture (Victoria: Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), pg. 11-12.

6Vicki Bennett, Sacred Space and Structural Style: The Embodiment of Socio-Religious Ideology (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1997), pg. 72.

Photos: Static

Undetermined, GROUNDS OF ST. ANN'S CONVENT, HEYWOOD AVENUE, VICTORIA, 1864, BC Archives, C-05380.http://www.bcarchives.gov.bc.ca

Return↩

Undetermined, St. Ann's convent, Victoria, 187-, BC Archives, C-07778.http://www.bcarchives.gov.bc.ca

Return↩

Photos: On Hover

Undetermined, ST. ANN'S CONVENT, ON KANAKA STREET AS HUMBOLDT STREET WAS KNOWN, VICTORIA, 1872, BC Archives, A-04992.www.bcarchives.gov.bc.ca