Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Rob Wipond

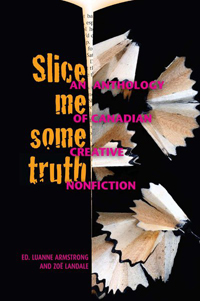

Luanne Armstrong and Zoë Landale (eds.), Slice me some truth: An

anthology of Canadian creative nonfiction. (Hamilton: Wolsak and Wynn,

2011). Paperbound, 350 pp., $29.

How do we define creative nonfiction? Editors Luanne Armstrong and Zoë Landale ask this in their preface to Slice me some truth: An anthology of Canadian creative nonfiction. It’s an important question, because the editors’ stated goal was to conduct a “thorough survey” and gather a “cross-section” of writings into “a comprehensive anthology that surveyed the genre as it presently exists in contemporary Canadian literature.” With such a broad goal, one would expect Armstrong and Landale to employ a broad definition of CNF. While there’s ongoing debate about finer nuances, most authors, post-secondary courses, academic journals, publishers, and literary awards programs loosely define CNF as fact-based writing that incorporates some techniques typically associated with fiction, such as characterization, plot, narrative voice, setting, or dialogue. In a contemporary Canadian context this typically includes, then, not only nonfiction from our literary journals, but everything from philosophical outdoor forays in Explore and investigative cultural features in The Walrus, to humorous memoirs in Zoomer, anecdote-driven profiles in BC Business, and text-and-graphic polemics in Adbusters.

For some, such diversity of form and style is to be welcomed and celebrated within CNF. The nominees for the 2013 Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-fiction, for example, include a biography of a poet, a journalistic investigation of the super rich, a reflective exploration into the quantum cosmos, and an insider’s account of being kidnapped. But Armstrong and Landale instead boldly proclaim that CNF distinguishes itself from journalism by virtue of the fact that “the writer appears front and centre in the work” and “the author is the hero of his or her own story.” Armstrong and Landale actually seem to be merely describing CNF’s personal memoir and immersion journalism subtypes, and it is unclear what they intended with this strict definition because they shortly thereafter express being “disappointed” that the majority of submissions for their anthology were personal memoirs. Yet what did they expect, given their limited definition of CNF?

In any case, only a handful of the thirty-six stories in Slice me some truth are not memoirs and do not revolve around the authors themselves. That comes with consequences, as evident amongst professionals as in a university writing workshop: if you have had incredible experiences, or are capable of dazzling levels of sensitive, thoughtful, descriptive reflection upon your experiences, then you may have a good story. Otherwise, you probably have a self-absorbed dud.

There are some fine stories in this anthology. There is Charles Montgomery’s, “The Moment of Knowing,” where a breathtaking ocean wave briefly takes on a tender, inspiring, and ultimately enduring role in two brothers’ diverging lives. The graphic account of an eighteen-year-old Evelyn Lau’s prescription-drug-drenched affair with a married, forty-three-year-old psychiatrist seems even more disturbing today than it probably would have decades ago, when few were familiar with prescription psychotropics. And right from the opening of “Dark Water,” Lorna Crozier stitches a texturally layered series of insights about the draws and dangers of marriage conventions: “My mother’s wedding dress, a rich blue-black velvet, flowed from her shoulders to just above her ankles. It had weight to it and a soft nap that invited you to touch and hold it like a liquid shadow in your hands. As a child, I used to climb inside the closet, where it hung in the back, and rub my cheek against it.”

Unfortunately, too often while reading this anthology of mainly previously unpublished works, one feels as if a rich vein beyond the authors’ own personal experiences was left untapped, when it could have added much to the stories’ dimensions and drama. This is particularly true, for example, when the story of a female applicant struggling through militaristic RCMP exercises includes no contextualization within the force’s notorious old-boys culture, or a memoir comparing life in Cuba and Newfoundland demonstrates little supplemental research into the geography, history, people, or politics of either. Other times, a travel or nature memoir meanders like an ordinary tourist jaunt dressed up with mildly likeable anecdotes and embellished language. That said, Armstrong and Landale suggest using this book in university courses, and an instructor could indeed effectively employ this anthology’s weaker personal memoirs to provoke discussion about ways to make the ordinary more stirring, reflections more informed, or content more compellingly expansive.

Notably, the most intellectually and dramatically engaging story is Sarah Murphy’s “La Pincoya”—and it also underscores the anthology’s main limitation. Amidst meditations on failing memory and the painfully unforgettable, Murphy, a translator of torture-victim testimonials, explores former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s possible trial in old age, the vulnerability of her own dying husband, and the role of news media and governments in either alleviating or exacerbating personal suffering. Murphy writes: “Were you raped is one of the easier questions. While the reporter just wishes to keep the story within the boundaries dictated to her, the time she has between commercials. The woman beside me just an instrument. Cynically, I sometimes think, to sell pop, or life insurance.” And while Murphy’s own story is mesmerizing as she deliberates what to commit to public memory, it mostly remains mercifully subordinate to the immense significance of the stories from others that she’s carrying. In that sense, “La Pincoya” comes to symbolize the many stories that go untold and unrepresented in Slice me some truth—stories from those who are not writers, but still deserve to have writers tell their stories and be appreciated as important contributions to Canadian CNF’s diversity.

—Rob Wipond