Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Susan Olding

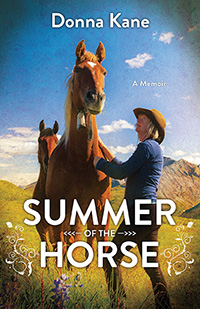

Donna Kane, Summer of the Horse (Madeira Park: Harbour, 2018). Paperbound, 208 pp., $19.95.

“You must change your life,” says Rilke’s Apollo, but few of us heed that call when it comes in middle age. Poet Donna Kane did, leaving a marriage of twenty-five years for the love of a white-haired wilderness guide and a Clydesdale-sized set of unanticipated responsibilities. In Summer of the Horse, her closely observed, meditative memoir, she reflects on the meaning of her seemingly impulsive decision with a pure and honest attention that celebrates the wisdom of the heart and penetrates the heart of wisdom.

“You must change your life,” says Rilke’s Apollo, but few of us heed that call when it comes in middle age. Poet Donna Kane did, leaving a marriage of twenty-five years for the love of a white-haired wilderness guide and a Clydesdale-sized set of unanticipated responsibilities. In Summer of the Horse, her closely observed, meditative memoir, she reflects on the meaning of her seemingly impulsive decision with a pure and honest attention that celebrates the wisdom of the heart and penetrates the heart of wisdom.

Attention begins as gift and later becomes Kane’s discipline. In the first flush of love, her senses are heightened, the beauties of British Columbia’s Muskwa-Kechika wilderness standing out in sharp relief and surrounding her like a benediction. High on the alpine trails that her new husband, Wayne Sawchuk, has laboured so hard to protect in his role as conservationist, caribou tracks “pestle” the scree, lichen crackles underfoot like “corn flakes” and “air is thin as a marmot’s whistle.” Every sound seems directed at her and every ripple of the wind urges her forward, away from her past. But later, when she trades the trail for the farmhouse, cooking for clients between expeditions and solving administrative problems while Wayne rides off for the summer, she begins to feel too heavily burdened by her unaccustomed duties. Then, she learns that attention is a kind of love, and love requires commitment as well as wonder, action as well as feeling. It is in caring for Comet, an injured gelding, that she puts those lessons into practice, becoming, in the process, the self she needed to change her life to see.

Kane blames herself for Comet’s wound. Preoccupied by organizing tasks for an arts festival and eager for a summer devoted more to writing than to chores, she forgets to check on the horses one night while Wayne is away; in the morning one of them is a bloody mess, his wound so deep she thinks she could “stick [her] head inside.” He’s lucky to be alive and will require twice-daily hosing and tending with medications for months. Kane is not a natural around horses, but she’s stubborn and refuses an offer of help from a horse-loving friend. Maybe she likes playing martyr and wants to punish herself for her mistake, or maybe, she reflects, she wants to prove something. In leaving her long marriage, she learned what it is to open a wound. Now she wants to know what it is to heal one.

Interspersed with the story of Kane and Comet are chapters that meditate on consciousness, on human/equine relationships, on wilderness and conservation, and on poetry and philosophy. Kane is an unpretentious yet erudite guide, who can talk with equal ease about the details of shoeing a horse and Plato’s allegory of the cave, thrill to the quintessentially North American sight of a grizzly or moose while summoning the plummy tones of Virginia Woolf with the image of a moth drowning in her merlot. Her descriptions of the natural world show a poet’s sensitivity to image and language. On one page, we might be focused on the subtle striations of an insect’s wing, on the next, we’re surveying a hundred miles of wilderness from the top of a mountain peak. These shifts in range and register make for a sometimes rocky and circuitous ride, much like the trails through the boreal forests that Kane has come to love—and much like life itself. Together, Kane’s varied points of attention add up to a holistic vision, one that can encompass Keats’s “mysteries and doubts” without any “irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

People who take the kind of mid-life leap that Kane did are often labelled “brave,” “crazy,” or “selfish.” We both admire and punish those who do what most of us don’t dare to do—especially women. But selfishness and madness and courage are sometimes beside the point. It takes a certain kind of faith in oneself to heed the soul’s inclinations and a special kind of grounded wisdom to follow through on the implications of those promptings. By leaping into an unknown future, Kane shows a rare and precious openness to experience. But it is by tending to her wounded horse that she demonstrates her true mettle. “In dreams begin responsibility,” wrote Yeats. Donna Kane’s journey from love-struck neophyte to loving partner bountifully illustrates the claim, for it is in learning to take responsibility for her choices that Kane becomes the woman and the writer she has been struggling all her life to become.

At the heart of everything is mystery, Kane reminds us. And that mystery is itself a kind of beauty, much like the wilderness. In Summer of the Horse, she takes us on an unsentimental, honest, and contemplative ride to the wildest outposts of the heart, and leaves us with a sense of wonder.

—Susan Olding