Reviews

Fiction Review by Jessica Rose

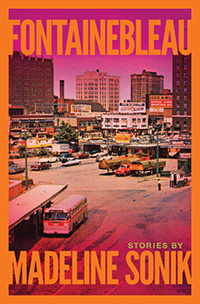

Madeline Sonik, Fontainebleau (Vancouver: Anvil, 2020). Paperbound, 204 pp., $20.

There’s nothing pristine about Fontainebleau, a mythical city perched on the Detroit River. It’s a wasteland—bleak and in disrepair—inhabited by crooks, delinquents, victims, and perpetrators. A tired city filled with tired people, Fontainebleau is the creation of British Columbia’s Madeline Sonik, an award-winning writer, anthologist, and teacher. Her engrossing collection of seventeen linked short stories is inspired by events that took place in Windsor, in the Fontainebleau subdivision of her childhood.

There’s nothing pristine about Fontainebleau, a mythical city perched on the Detroit River. It’s a wasteland—bleak and in disrepair—inhabited by crooks, delinquents, victims, and perpetrators. A tired city filled with tired people, Fontainebleau is the creation of British Columbia’s Madeline Sonik, an award-winning writer, anthologist, and teacher. Her engrossing collection of seventeen linked short stories is inspired by events that took place in Windsor, in the Fontainebleau subdivision of her childhood.

Beginning with “Air Time,” a story reminiscent of life before selfisolation, when “amber light glints off bottles of bourbon and rye,” Fontainebleau sets its foreboding tone. Seated in the local bar, Mike and Steve, two sleazy, disreputable men, prod two teenage girls to “Chuga-a-lug, Chug-a-lug” to excess, with the intention of drugging them. It’s only the first of many times Fontainebleau’s impeccably crafted, but ugly tales will make readers feel unsettled. Visceral and violent, the collection will introduce them to many sordid characters, among them snuff-film producers, young offenders, hard-drinking and tough-talking locals, men who hurt women, and those who fantasize about it.

Despite being populated by troublemakers, like Tony Deluca, who leaves “bags of flaming dog shit on porches, terrorizing resident felines and tagging, with black spray paint, the windows of the portable classrooms at his former public school,” Fontainebleau itself is the collection’s most fascinating character. With great ease, Sonik contrasts the weathered, battered location with her dazzling prose, giving life to a swelling city bordered by desolate farmland. “Beginning where the gravel road grew vague at the end of Monica Street, the field spread lake-like. It opened past the dying maples, the reedy swamp, the abandoned and twisted mufflers of the car graveyard, past a grey shack, out in waves of swelling stink grass, to the sooty oil-soaked spines of the railroad ties,” she eloquently writes in “The Mermaid,” a story about Celeste, one of the collection’s more sympathetic characters, who has mermaid syndrome, an extremely rare congenital developmental disorder.

Linked by their locale and characters who disappear only to reappear (sometimes dead, sometimes alive), the stories in Fontainebleau intersect, employing common, permeating elements. Among these are throngs of scrutinizing crows and trains that groan along a track near the highway, their whistles bleeding into the sky. Themes,

including isolation, memory (or lack of memory), marginalization, and discrimination appear frequently in the collection. Survival, still another theme, is both figurative and literal. In the literal sense, Jimmy, a character in “Flight,” the book’s chilling fourth story, finds himself stranded, trapping chipmunks and field mice to eat, later carving a bow from a branch. Some characters in Fontainebleau don’t survive, dying in freak accidents or by someone else’s hand. Others run, searching for redemption or escape.

Despite the commonalities, there are differences, each story eliciting a unique emotional response. Most notably, tone, voice, and point of view shift effortlessly from story to story, providing variety uncommon from a collection authored by one person. What makes Fontainebleau especially unusual is glimpses of the supernatural, used sparingly. In one moment a character might be rooted to the ground, only to find himself soaring through air: “Maybe he should have stopped—shown them that he wasn’t afraid—but the muscles in his legs began running, and the bones of his feet came away from the earth. There were corn tassels in front of his eyes as he ascended, bending and bobbing, flinging sticky pollen everywhere, and crows, which he suddenly realized, were intergalactic rovers spying on earth” (“The Boy Who Flew”). Both human and avian flight factor heavily in Fontainebleau. “A frightened pheasant concealed in the sedge took flight, its wings like oars in a river of sky and its brown feathered body like an ascending angel’s,” she writes in “Murder,” one of the collection’s most memorable stories.

Deeply inventive, Fontainebleau is undoubtedly unlike anything you’ve read before. Oozing with murder, mystery, and characters so atrocious that one often wants to turn away, it is grim and ghastly, offering little optimism for Fontainebleau or its inhabitants. Yet through Sonik’s skillful, graceful prose, there are moments of pure

joy. In “Makeover,” Margaret, a chambermaid at the River Park Hotel, tries on a guest’s wig and red dress: “There’s a sturdiness about her, a charismatic amplitude, a power she possesses, but one she’s never been aware of. Had she always walked with such confidence? Had she always been so tall?” The moment offers a rare glimpse of levity in which one of Fontainebleau’s despondent residents feels a tiny bit of hope.

If you like tidy, happy endings, Fontainebleau will likely disappoint you. Good rarely prevails over evil, nor will readers expect it to. Instead, Sonik’s immaculate storytelling will thrill those who delight in the macabre, the disturbing, and the bleak. Juxtaposing the real and imagined, her sublime sentences guide readers through characters’ lives, deaths, and sometimes resurrections. Set against the backdrop of a cold, crime-ridden city, it’s a book about impulse, misfortune, and secrets that are begging to be revealed.

—Jessica Rose